The Stahr system

By Michael J. Roberts

"I Think there should be collaboration, but under my thumb."

~ Elia Kazan

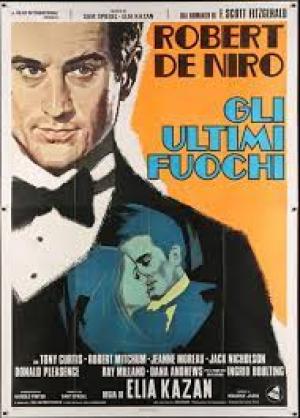

After a distinguished and controversial 30 plus year career as a director in both theatre and feature film, Elia Kazan went out with a low-key adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s final novel, The Last Tycoon, a melancholy valentine to the movie business. The downbeat tone of the piece was Pinteresque for a very good reason, as the adaptation was indeed written by Harold Pinter, who captured the quiet desperation and fading grandeur of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Kazan tapped Robert De Niro to star as the wunderkind producer Monroe Stahr and rounded out the cast with a mix of relative newcomers like Theresa Russell and veterans like Robert Mitchum, Dana Andrews, Ray Milland and Tony Curtis, and added Jack Nicholson to the heady mix for maximum effect.

Monroe Stahr (Robert De Niro) is the hot producer for a major Hollywood studio in the 1930s, with an unerring sense of what the public will flock to and thereby fill the company coffers, making him a valuable asset for his boss Pat Brady (Robert Mitchum) and for the Wall St. money men they both answer to. Stahr is a workaholic who has thrown himself even deeper into his work following the tragic and premature death of his girlfriend Mina, a famous actress. He becomes infatuated with Kathleen (Ingrid Boulting) who is the double of his dead girlfriend, and in between his attempts to woo her he battles the studio, the money men, a writer’s strike and the unwanted attentions of his boss’s daughter Cecilia (Theresa Russell).

Kazan intimately knew the Hollywood types he was dissecting here, with the skill of a veteran vivisectionist, when he laid down his final frames in partnership with his On The Waterfront producer Sam Spiegel. Kazan worked at the pinnacle of old Hollywood and it’s fitting that he offered his take on the movie business towards the end of the so-called New Hollywood of 1967-1980. Kazan’s innate cynicism gelled well with the dream-like tone of the script, and in many ways the film is a fine companion piece to John Schlesinger’s brilliant Day Of The Locust from the year before, as both capture elements of the kind of clawing delusion and sputtering madness that lurked not far below the gloss.

Pinter beautifully and subtlety distills the paradox at the heart of the piece - the contrast between the ephemera of pop culture and the quasi-immortality that the silver screen conferred on the lucky few. Stahr may be a golden boy, but his success walks on quicksand, and what is gifted by the public is so often easily withdrawn on a whim. Movies at that time had one measure of success, box-office take, and even great directors like John Ford would often dismiss their own work if they ‘failed’ at the box office. Stahr lives and dies by this empty mantra, and eventually chases something more real than the chimera of reflected silver screen sheen in a real connection with a mysterious woman. He longs for Kathleen, but what she offers is equally chimeric, equally elusive and the banal reality of her situation eventually prevails over his illusive yearning. Stahr is forever dissatisfied and incomplete, reflected in his work experience and rendered in metaphor via his unfinished dream house that Kathleen will never live in.

Kazan populated the film with a fine supporting cast, and old Hollywood stalwarts like John Carradine, Ray Milland and Dana Andrews popped up along with wonderful character actors like Jeff Corey and Donald Pleasance. Pleasance all but steals the film with his oddball writer character, but Jack Nicholson runs him close with his screen eating cameo. Jeff Corey’s presence is an odd reminder of the Hollywood Blacklist, given he was one of its victims and Kazan one of the most notorious ‘namer’ of names. Ingrid Boulting is ideal as the non-entity Kathleen, even though critics gave her a hard time given she lacked acting ability (and promptly disappeared off the radar as an actress), ironic given she was from a distinguished British film family. Theresa Russell made a mark in her feature debut and would go on to a solid career, mostly in league with her future husband, director Nic Roeg.

The film’s fortunes rightly turn on the dominating figure of Stahr, and more particularly on the characterisation of Robert De Niro. Stahr is a messianic figure for the studio, a King Midas who has tapped the fickle public consciousness and embodies the ‘great man of history’ myth, the lone saviour, the sure thing. In a world where making a film is a costly gamble, having someone who can interpret the runes and master the dark arts is money in the bank. Until it isn’t. De Niro underplays the character, and part of the reason the film’s reputation didn’t attract the same Midas lustre was that in the same year De Niro also delivered to the screen one Travis Bickle. Stahr never stood a chance in that shoot out, but it remains an example of an actor at the top of his craft on a hot streak that remains one of the greatest in all of cinema. De Niro is compelling as Stahr, and he always rated his experience with Kazan as amongst his best with any director. He returned the debt in 1999 when he publicly stood behind Kazan at the Oscars ceremony as Kazan was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award amid great controversy arising from the director’s HUAC testimony.

Kazan created a quasi-tone poem with The Last Tycoon, a mostly bitter rumination on the folly of commerce attempting to wrestle the ‘lightning in a bottle’ nature of art. It’s a subtle condemnation and acknowledgement of the madness of money following the quixotic mercury of creativity and in its foolhardy attempt at expecting to standardise the ‘product’ like a Henry Ford assembly line. The Dream Factory paradox is personified in the empty vessel that is Kathleen, all surface beauty from afar and deathlessly ordinary underneath. When one assembly line head fails, you can get a new one, but when one visionary messiah loses his magic, it’s not so easy.

A troubled and difficult man, Kazan settled into writing novels in his old age, and also managed to spew out the astonishing and bracing autobiography, A Life. Once read, never forgotten. The meditative tone of this film, shot beautifully by John Cassavetes alumnus Victor J. Kemper, proved too problematic for movie audiences in 1976, but it has stood the test of time and indeed got better with age. The Last Tycoon remains a first class if downbeat meditation on life in the Dream Factory once upon a time.