Myth meets mysticism

By Michael Roberts

'If you can’t do it without relying on the spoken word, you’re not doing it visually, and that’s what I intend to do.' ~ John Ford

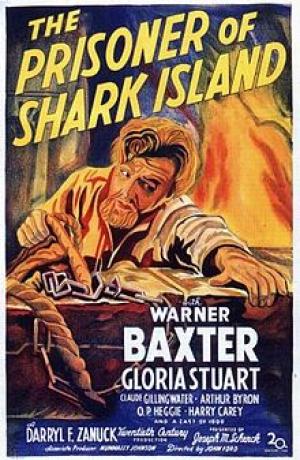

There exists in John Ford’s work and mise en scene, as there does in Hitchcock’s a confluence between a mannered and staged approach, which when crossed with a formal visual style creates a subtle, surreal panorama, an altered reality where it’s still possible to believe we are looking at the going’s on of men and women from our side of the silver nitrate divide. The Prisoner of Shark Island, is such a film, creating as much myth and mysticism, as documentation or reportage, oddly befitting for such an historically inaccurate piece of entertainment. Nunnally Johnson, then a house writer for Zanuck at Fox wrote the script after Fox bought the rights to a book on Samuel Mudd by one of his daughter’s, the book was uncredited in the film and, after Johnson condensed and manufactured the truth as he saw fit, it was just as well.

Ford opens the film with one of the great gestures of sympathy and consolation in American history, a war weary Abe Lincoln’s request, in the face of a triumphal crowd at the end of the civil war, for the band to strike up ‘Dixie’. Come back Abe Lincoln, come back to us now…. One week later, we’re at Ford’s Theatre watching John Wilkes Booth sidle in and do his deed. Ford avoids making Booth a caricature villain, there’s almost regret before he pulls the trigger, and his covering of Lincoln’s face with a tapestry gauze as the camera pulls out of focus creates a visual elegance that signifies a genius at work. Booth gets help for his broken leg from Mudd during his escape and this is enough to convict him, according to the film, of being involved in the conspiracy. Mudd claims he was following his oath as a doctor and in any case had no knowledge of the shooting. Mudd is sent to a rugged penal island in the Dry Tortuga’s in the Gulf of Mexico. While he’s there he tries to escape with the help of one of his former slaves Buck, and swims through shark infested waters to a boat his wife has arranged. Mudd is captured and taken back to Solitary confinement. During an outbreak of yellow fever the prison commandant asks Mudd to help minister to the sick, as the regular doctor had come down with the disease. Mudd battles through, getting sick in the process but earning respect, even from the hardened Sergeant who had persecuted him since he arrived. A petition is sent off and Mudd is pardoned and arrives home to his faithful wife and child.

The story is not much more than a framework for Ford to make a film about an innocent man being railroaded by a corrupted judicial system. The part of the film that holds enormous interest for post 9/11 audiences occurs just before the trial and during it, about 22 minutes in, and those few minutes should be mandatory viewing. Ford has the Secretary of State, having decided on a court martial instead of civil proceedings, address the presiding military officers and tell them they are to ignore such legal niceties as ‘rules of evidence and reasonable doubt’, he opens the window so that they can hear the bloodthirsty mob below and asks that they hear the ‘will of the people’. The defendants are led into the courtroom looking like they have come out of Abu Ghraib or Guantanamo Bay in 2004! The event of Lincoln’s assassination was so traumatic the authorities arbitrarily decided that ordinary people could not be trusted to allow the usual course of law to be followed, and perverted the system to contaminate the outcome. Of course these same politicians ensured their own aggrandisement in the process and entrenched ideas that degraded public and private freedoms. Sound familiar? plus ca change.

Ford constructed a visual language for the film reminiscent of his great hero Murnau, and the scenes in the prison and on the island have a precision and a depth that affirms his great command of mise en scene. Warner Baxter plays Mudd, and does a reasonable job even if his style has dated slightly. Oddly a massive argument erupted on set between Zanuck and Ford over the broadness of the southern accent Baxter was using. Nunnally Johnson was a southerner and told Ford it was too extreme and would be a disaster for southern audiences who would feel it was demeaning them, and after Ford had no luck in reigning Baxter in Zanuck came onto set and did it for him, threatening to fire Ford in the process. Ford and Zanuck continued to work well however, and in that stint between the mid 1930s and early '40s Ford did 12 pictures at Fox. Zanuck remained one of the few people Ford called a ‘genius’ and meant it. One actor’s work who didn’t date was Harry Carey, one of Ford’s oldest friends who was a big star in the early silent films when Ford was just starting out, Ford had him play the Commandant and his is a lovely and moving portrayal of depth and authority. Mention should be made of the brilliant John Carradine as the brutal and obsessed Sergeant, who ultimately sees that Mudd is a decent man, not the monster who killed the ‘greatest man who ever lived’.

Historically it's all over the place, given there’s no clear verdict on the level of Mudd’s complicity (mostly due to the fact that the investigation was rushed), plus the fact that evidence not fully pursued, the trial was flawed and limited in scope in wanting to get a quick political result that people were happy with rather than the ‘truth’. The Prisoner of Shark Island is nonetheless first rate Ford, and that means it’s required viewing for anyone interested in classic cinema.