So good he made it thrice (I love it)

By Michael Roberts

Howard Hawks had a three year sabbatical in Europe after his 1955 epic Land of the Pharaohs failed to do well and had to re-start his career in a sense with Rio Bravo, a film he then more or less remade twice with El Dorado and Rio Lobo before retiring from directing in 1970. Hawks had been a remarkable survivor, he directed 6 silent films before his first sound feature in 1928, and had been responsible for producing classic examples in many genres in the years between his start and Rio Bravo, but by 1958 the ornery contrarian was seemingly running out of steam, and the fact that the three ‘western in triplicate’ pictures mentioned represented half his output in his final dozen years as a director confirms how bereft of idea’s he became. Hawks created a significant body of work though, so the dearth of originality may be forgivable to some degree, but what occurred in Rio Bravo’s artistic and commercial success was in many way’s unexpected as no-one in the industry was keen on a big budget western feature film given television’s saturation of the form at that time. Hawks produced a masterly work, a deeply personal statement that was comparable to that of his great friend John Ford’s slightly later and very personal The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, but whereas Ford’s film had a certain Fin de siècle about it, Hawks preserved an era and a type of hero in aspic, to be taken out and marveled at when reassurance of old values and certainties were needed.

An egotist of the first order Hawks had the natural confidence knocked out of him by the public’s rejection of his contribution to the ‘sword and sandals’ cycle so popular in the ’50’s, and it’s no surprise he retreated to the familiar territory of the west. Hawks only managed to have the project green lighted by Warner Brothers after he secured John Wayne as the star, a huge draw card but who was himself in need of a hit. Hawks engaged the same top writers that he had turned to for his The Big Sleep in Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett. Furthman’s experience stretched back to 1915 and this would be his final film and the last of eight he worked on for Hawks, matching his eight collaborations with cinematic visionary Joseph Von Sternberg, who’s 1927 gangster flick Underworld Hawks had worked on. Hawks filmed on location near Tucson with another Red River veteran, cinematographer Russell Harlan, who brought a crisp and clean palette to the dusty desert ambience. Wayne plays one of his iconic roles, sure and steady and in a way few others could, and Dean Martin is fantastic as his alcoholic friend. Walter Brennan made it a hat trick of key Red River personnel, and his ‘teeth out’ performance thankfully doesn’t chew anything in relation to scenery, as it hits just the right counterpoint in the male chorus.

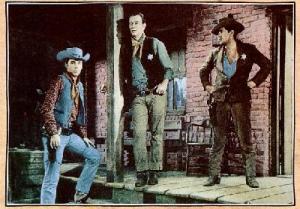

Hawks gets back to his silent roots with the first scene, showing an essentially visual sequence involving deputy Sheriff Dude (Dean Martin) scavenging for a drink in a saloon, desperate, disheveled and shaking, only to be insulted and goaded by villain Joe Burdette (Claude Akins). Sheriff John Chance attempts to intervene but is knocked cold by Dude, who is then beaten up by Joe, an un-named stranger tries to help and Joe shoots him in the gut in cold blood. Without one word of dialogue Hawks has created a fully understood and detailed world. Chance comes too, and he and Dude arrest Joe and put him in gaol to await the US Marshal next week. Joe’s brother Nathan hires gunmen to lock up the town while Chance waits, and a stand off ensues that sees the two lawman, plus an old deputy called Stumpy (Walter Brennan) have to hold off against a posse of mercenaries.

Televisions influence is apparent as Hawks takes a long time to establish character at the expense of action. He intuitively understood that viewers were now conditioned by weekly installments of regular shows to emotionally invest in the characters and their dilemmas, therefore the pace of Rio Bravo is deliberately slow and it gives Hawks room to layer in detail and nuance that pays off handsomely in the end. After the initial premise is understood Hawks takes a pot shot at one of his and Wayne’s bugbears, the behaviour of Gary Cooper’s lawman in High Noon, and one of the driving motivations in making Rio Bravo the way he did. Hawks was famously dismissive of the liberalist western where the ‘professional’ lawman seeks help against an approaching gang of revenge seeking outlaws, he thought the act ridiculous and that a ‘professional’ man would ever seek the help of ‘amateurs’. Wayne called High Noon un-American, and relished speaking the lines "I don’t want help from a bunch of well meaning amateurs", even though he notionally only had a drunk and a cripple as his back up.

To spice up the situation Hawks introduces two younger characters into the veteran professional’s world, Feathers (Angie Dickinson) and Colorado (Ricky Nelson). Feathers is a saloon girl hustler who Chance tries to run out of town, and Colorado is a fast gun who eventually sides with the Sheriff. Feathers fits the bill for the typical ‘Hawksian’ woman, she’s strong willed and independent, and needs to find a man who is strong enough to handle her, which she does in Chance. The Hawks woman wants the man to be a man, and understands the conflicting impulses that type of man has to deal with, but she’s smart enough to know she needs to love him for who he is. "You said you love me", says Feathers, "I said I’d arrest ya" bleats Chance, "Same thing", she replies. Alternately she will have something about herself she’ll typically want him to object to and therefore give her the chance at fundamental change, with Feathers it’s her job as a saloon singer. Colorado’s character allows the opportunity to show how the Hawks group can bond, and for that Hawks made use of the fact that he had two popular singers in the roles with Martin and Nelson, and they provide a lovely cowboy song duet, with Brennan on harmonica, in ‘My Rifle, My Pony And Me’.

In the final analysis, with all it’s technical proficiency, careful crafting and Hollywood polish, Rio Bravo is most of all a film about deep male friendship through the relationship of Chance and Dude, and of the redemption that the friendship makes possible for Dude. It’s this quality above all that helps elevate it beyond an ‘extended TV episode’ and takes it into the realms of artful insight. As with the central relationship in Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings from 1939, where Geoff (Cary Grant) ‘loves’ the troubled Kid (Thomas Mitchell) so it is with Chance and the troubled Dude. Furthman also wrote the earlier piece, which was very in tune with the fatalism found in the French poetic realist films of the era, indeed it may be one of few American films that could fit that sub-genre, whereas Rio Bravo is a film for the Eisenhower era, where the values of an earlier time speak to what is lacking in the present. Consumerist 1950’s America, rampant and unfettered had created an environment where what you had in terms of material things was deemed to be more important than the foundations of a society that was failing to put conspicuous consumption into perspective. While Hawks was not a political filmmaker he had found an era where his message of traditional values of courage and friendship could find resonance in a culture broadly unaware of the emptiness at the core of it’s pyrite heart.

Rio Bravo is a knockout at every level, a reminder that John Wayne with the right director is peerless, and there’s even a tribute shot to The Searchers as Wayne’s graceful form is unmistakably framed in a doorway during the final showdown, surely a reverent little nod to Ford from Hawks? Rio Bravo is a carefully paced joy to be savoured, and it’s also a beautiful long-form-essay summation of the career of one of Hollywood’s survivors, consummate technicians and compelling personalities in Howard Hawks.