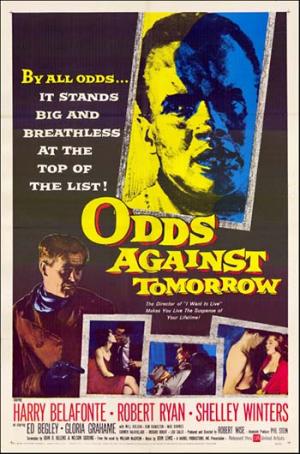

Heist noir

By Michael Roberts

'You can't tell any kind of a story without having some kind of a theme, something to say between the lines.' ~ Robert Wise

As fascinating and important a film as this is in many ways, it should not obscure it’s value as an engrossing, gritty and lowdown ‘heist-noir’ made after the genre had notionally at least come to a close with Welles’ Touch Of Evil the year before. Robert Wise directed with verve and precision a script by blacklisted writer Abraham Polonsky, thanks to use of a front or ‘beard’, ironically in this case John Killens, a black novelist friend of producer/star Harry Belafonte’s. The film was released during the pivotal years of the civil rights struggle, a cause on which Belafonte was to take centre stage as one of show-business’ leading liberals. The film was shot on location on the Upper West Side of New York and makes stunning use of it and the Central Park surrounds, as well as the semi-rural small town further up the Hudson River where the target bank is located.

Dave Burke (Ed Begley) is a bitter ex-cop in need of money from one big robbery to put his fractured past behind him. He attempts to enlist a couple of accomplices in his planned heist, the first an emasculated failure of an ex-con named Earle Slater (Robert Ryan) who is interested in doing something to make his fortune before time runs out. He’s married to Lorry (Shelley Winters) who suffocates him in ways more befitting a mother, controlling every detail of a life that has devolved into a mess of frustrations. The other mark that Burke targets is a black nightclub singer Johnny Ingram (Harry Belafonte) who rejects the idea at first, even though he owes a lot of money to Bacco, an underworld figure, due to heavy gambling losses. Burke secretly approaches Bacco to lean on Ingram and call in the debt, something he hadn’t done before but would force a desperate Ingram into the heist. Burke cases out the bank with Slater, who is also unconvinced of the merit of the scheme. The fly in the ointment is that key to gaining entry into the bank is that they will need a black delivery boy to carry the coffee and sandwiches the workers order regularly and Burke discovers Slater in an unreconstructed racist.

Ingram is singing in a Harlem nightclub when Bacco and a couple of henchmen walk in, one a markedly gay character who flirts with the singer! Ingram tries to get the owner to bail him out of the debt but he refuses, causing Ingram to agree to the heist. In a scene with his estranged wife there’s a heated exchange about servitude to white master’s and Ingram makes plain that he wants his daughter to grow up in such a way she never belittles herself, insinuating that his wife Edie (Lois Thorne) attempts to be a ‘see-through’ or ‘opaque’ black, doing what is needed to blend in and climb the white dominated social ladder. Slater further feels his ‘manhood’ threatened by running menial errands for Lorry and gets into a bar fight, his hot temper recalling many incidents in his past that have forced him to ‘walk away’ from every situation he can’t handle. Lorry is out at night, earning a living to support him but he seduces the upstairs neighbour (Gloria Grahame) who is drawn to his chequered past. Slater determines he has no choice but to ‘out-provide’ Lorry and despite his hatred of ‘niggers’ he agrees to the heist.

The men meet in the town, tellingly Ingram has to take a bus while the white men drive in private cars, the social fabric in action. tensions erupt prior to the heist between Slater and Ingram but both men know they have made a pact with the devil in order to work together and will see it through. The heist gets under way at the appointed hour, and Wise handles the build up and execution without fuss, milking the tension and suspense with concise set ups and cutting. Of course the robbery falls apart as Burke is seen exiting the bank’s side door by a patrolling cop, when challenged he starts shooting and all hell breaks loose. Ingram wants to help the injured Burke into the getaway car, but Slater writes him off and runs for it, incensing Ingram. Oblivious to the police that are tailing the pair Ingram tracks Slater to a petrol storage site and when they exchange fire atop the tanks they are both incinerated in the explosions. The police extract the charred corpses and are unable to tell which is Ingram and which is Slater.

Robert Wise reunited with the star of The Set-Up his 1949 boxing noir, Robert Ryan, a staple of the genre and Ryan delivers his usual powerful and committed performance. Belafonte, a giant of a human being, is excellent as the reluctant criminal and gives emotion and depth to the issues of race that lie at the centre of this stark piece. Begley represents the corruption of his generation, unable to shape a society where opportunity is equally available to the coloured kids we see parading on the street outside his apartment at the start of the film. Ingram’s inability to control his own weakness contributes to his lack of options and in the end all three gang members are equal in their impotence, but the black man more equal that the others.