Gilliam gets Orwellian

By Michael Roberts

“Well, I really want to encourage a kind of fantasy, a kind of magic. I love the term magical realism whoever invented it – I do actually like it because it says certain things. It's about expanding how you see the world. I think we live in an age where we're just hammered, hammered to think this is what the world is. Television's saying, everything's saying 'That's the world.' And it's not the world. The world is a million possible things”. – Terry Gilliam

Terry Gilliam found his independence from the Monty Python troupe in the late ‘70’s with his Lewis Carroll sourced debut solo feature Jabberwocky, and followed it with Time Bandits, both sweet natured and family friendly fantasies. Brazil marked a turn towards a darker and more cynical style, one that would become a signature tone for Gilliam, and one that would ultimately prove to be harder to market than his more whimsical fantasies. Brazil was budgeted at three times that of Time Bandits and afforded Gilliam a much larger canvas on which to paint, and pointed the way to his grander visions with The Adventures of Baron Von Munchausen. Gilliam stated that he sees those three films as a ‘Trilogy of Imagination’, with Time Bandits showing the imagination of youth, Brazil middle age and Munchausen an old man. Gilliam co-wrote the script, with deliberate overtones of Orwell’s 1984, with Charles McKeown and playwright Tom Stoppard.

A slapstick level sequence opens the film where noted musician Ray Cooper plays a low level bureaucrat who swats a fly; it falls into a machine processing Ministry of Information files and causes a mistake to be made. Sam Lowry (Jonathon Pryce) is a daydreamer, a talented but underachieving bureaucrat who discovers the mistake and sets out to make amends of behalf of his nervous boss (Ian Holm). The error caused a family man to be arrested, interrogated and killed, and the activist neighbour Jill (Kim Greist) is pursuing the government for reparation. Sam becomes obsessed with the elusive Jill, and takes a promotion to the Department of Information Retrieval in order to find out more about her. Eventually Sam’s activity allows him to cover for the suspected terrorist action Jill has been engaged in and the couple enjoy a passionate night together before the system catches up with them.

The 1984 nightmare is one that resonates with Gilliam, and the uber-bureaucratic, totalitarian wasteland he presents is a neat companion world for Orwell’s dystopia. Gilliam creates a solipsistic sci-noir that owes a debt to German Expressionism as well as Film Noir, and one to the drab and pinstriped tribes of the British Civil Service. Sam is an ‘everyman’, trying to keep his head down and not get noticed; unfortunately his pushy and well connected mother (Katherine Helmond) has grander plans for him. Sam takes advantage of his mother’s influence once he finds something worth bothering about, i.e. Jill, the girl of his fantasies. Sam daydreams of being a winged knight, smiting great warriors and rescuing the damsel in distress, one that looks like Jill.

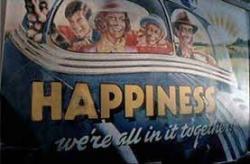

Sam embraces a ‘herd mentality’ when we first meet him, neither out in front and fearlessly leading the way nor at rear to be picked off with the stragglers, just happy to keep his head down in the middle and not get noticed. Sam is jerked out of his somnambulistic existence by his interaction with Jill and the effervescence she represents. Jill’s energy is fuelled by anger at the injustice wrought by the mechanical nature of the bureaucracy that controls every aspect of modern life, in a world where “you can’t make a move without paperwork”. She fights back against the rigid and ordered numbing routine, injecting a note of unpredictability, and chaos and excitement, into an environment that Sam had come to accept. Jill challenges Sam’s torpor, and he drags himself out of his ‘sleep’ to embrace his ‘dream’. Gilliam himself said Brazil was about "The craziness of our awkwardly ordered society and the desire to escape it through whatever means possible”.

Brazil also makes a subtle point about the banality of evil via the characters of the Deputy Minister Helpmann (Peter Vaughan) and Sam’s old friend Jack (Michael Palin). Helpmann’s opening monologue is priceless, he is commenting on terrorism acts and is asked what is behind the bombings, “Bad sportsmanship” he thunders, and complains about the guerrilla tactics in terms of a cricket match, pure British upper class twit. Jack betrays Sam as a matter of course, and Palin’s bloodless portrayal adds a layer of sinister gloss. Jonathan Pryce has the role of his career in Sam, and makes the journey from satiated office drone to tremulous dreamer with aplomb and verve. Kim Greist does less well as Jill, but is effective if not mesmerising. Robert De Niro plays a bizarre cameo and Bob Hoskins and Derrick O’Connor have great fun as bumbling technicians.

Gilliam effortlessly evokes the past and the future with Brazil, fitting into a genre loosely known as Retro-futurism, typified by Godard’s Alphaville, and more recently by Andrew Nicol’s Gattaca. One of the working titles for the project was 1984 ½, an acknowledgement of the equal debts to Orwell and Fellini the film owed, as typified by the flying sequence which recalls Fellini’s bravura opening to his masterpiece 8 ½, Gilliam’s acknowledged favourite film. Gilliam extends his visual language in cinema beyond the sometimes smell-of-an-oily-rag level of his first solo features and manages some astounding sequences with the much bigger budget. Even so it’s the poetry of the visual language that stays in the mind, and the movie is an idea driven, rather than ‘effects’ driven vehicle.

Brazil is a fine noir tinged, futuristic, solipsistic question mark, and Gilliam leaves very little room for hope in the downbeat ending. Sam resembles Icarus in some of the flying sequences, and ultimately he flies too close to the sun to survive, left a dribbling, vacant void enveloped in his own fantasies. The film is full of casual brilliance in its cascading array of memorable images and stylish tropes that pointed the way to the outrageous visual constructions Gilliam put on the screen a few years later in The Adventures of Baron Von Munchausen. The film is also a prime example of Magical Realism, a genre that took wings under the French duo of Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro in the late ‘90’s with Delicatessen and City of Lost Children, as well as Jeunet’s solo gem Amelie. Charlie Kaufman remains the pre-eminent source for material that fits that categorisation in America with brilliant examples such as Being John Malkovich and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Michael Radford’s worthy film version of Orwell’s 1984 was released 4 months prior to Brazil, and stole a march despite being an inferior film, and Brazil did not do well in the US after Universal fell into dispute with Gilliam about the cut. The incident is captured in Criterion’s DVD must see extras documentary, The Battle of Brazil, and explains Gilliam’s problems in the US. The film was embraced in Europe and remains a favourite in best ever lists from the BFI on down. Brazil is a singular vision, a viscous swipe at Fascism everywhere and a treat for CGI weary eyes…. on a sticky wicket Gilliam hits it for six.