Hey represto! Jung pushes Fellini from neo to magical realism.

By Michael Roberts

"Fellini's film is complete, simple, beautiful, honest, like the one Guido wants to make in 8½" – François Truffaut

Federico Fellini found himself at the apex of his career and critical acclaim after La Dolce Vita took the film world by storm in 1960, when a crisis of confidence about what to do next led to him making the best film about artistic block ever made, ironically enhancing his already giant stature by winning him his third Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Fellini felt cornered by success, with an entire industry depending upon him to come up with his next masterpiece, or as one character dryly says to Guido, the Fellini figure in 8 ½, “another film without hope”. Fellini said, “I was in limbo, taking stock of myself I needed to reconcile my fears. It would be a summoning up of dreams, recollections, forgotten feelings, shadowy doubts, and a kind of eternal quest for self knowledge and acceptance.”

Key events informed the new film, not least the discovery of the work of Carl Jung and the significance of his concept of ‘collective unconscious’, that dreams were not necessarily an individual’s Freudian sexual indicators but ‘archetypal images surfacing from a reservoir of common experience’. Fellini taped a small note to the camera at the start of the production that read, “Remember that this is a comic film”, but the end result is much more complex and nuanced than pure comedy. Called 8 ½ because it was that number film in the director’s output (his first feature was co-directed by Lattuado), Fellini had initially wanted to call the film Comedy, but its working title was far more apposite and revealing, The Beautiful Confusion.

Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) is a burnt out feature film director trying to recover his health at a popular spa, while contemplating the problems of his next project, a science fiction film. Guido juggles the demands of producers and technicians and those of his mistress Carla (Sandra Milo) and wife Luisa (Anouk Aimée), while he contemplates how he can extract himself from his artistic stasis. Guido takes the ‘cure’ at the spa, and finds he has to also deal with flashbacks to his childhood and residual issues with his parents, particularly his mother, that influence his dealings with the many women in his adult life. Increasingly he struggles to supply his producer and crew with answers to their many questions, while he dreams of a perfect life where all the women he has loved love him unconditionally. Eventually his dream woman arrives in the shape of an actress called Claudia (Claudia Cardinale), but disturbingly she seems to see through Guido’s charm and guile.

A central thesis in 8 ½ holds that if Guido is unable to control his life, at least he can control the film he’s directing, but when the line between film and reality blurs, when the line between dream and real life also disintegrates, then Guido falls into ‘director’s block’. Fellini frames the dilemma in Guido’s question to himself, “Is it a crisis of inspiration or the final collapse of a filthy liar”? When Guido is finally confronted with his multiple infidelities and duplicity by his long suffering wife he tells her “It’s only a movie”, to which she replies, “A movie is just another lie”. Guido fronts a chaotic press conference to promote the forthcoming, though yet non-existent film, and after hearing the threats of the producer and the derision of the cackling journalists, “He's lost! He has nothing to say”! Guido imagines ending it all with a gun, before he encounters all the characters in the film getting together for the famous final sequence.

Religion, (the beautiful lie) of course, lies like an invisible shroud over the narrative, impossible to escape in heavily Catholic Italy, and a key part of Fellini’s past. In a sweet echo of his own sepia tinged I Vitelloni, Fellini takes Guido back to his childhood and an encounter with Saraghina, a large prostitute on a beach, who dances for money for the schoolboys. The spark of real life that Guido enjoys with his school friends is soon ended by his teachers and priests, who punish and humiliate Guido. Obviously Guido is troubled by the idea he’s selling out his artistic integrity when the adult Guido is asked “Could you create something beautiful and real on commission, say the Pope for example”? The conflicting impulses of desire and guilt provide Fellini with a key psychological driver in relation to his protagonist, and underscores Guido’s inability to act decisively.

Guido goes to a Cardinal to seek advice, having been told by a priest “You mix profane and sacred love too casually”, but he only dreams of the Cardinal’s elliptical advice, proffering Origen’s dogmatic declaration “There is no salvation outside the church”. Guido’s writer friend provides advice on Catholicism too, “Your intention is to denounce, but you end up supporting it, like an accomplice”. The guilt that Guido was made to feel in relation to sex by the puritanical Catholic culture, where women are presented as destroyers of men’s higher selves by eliciting base desire, lies at the heart of his troubles with women. Fellini said, “After reading Jung I feel freed and liberated from the sense of guilt and… inferiority complex”. Jung’s theory implied that Fellini’s dreams were not aberrant, but creative, and the director grasped the idea as a kind of absolution, wiping out the guilt of his Catholic upbringing and his embarrassment at his poor education.

Guido delivers what could be a Fellini manifesto during a moment of self analysis with his wife’s best friend, “I wanted to make an honest film, no lies whatsoever. I thought I had something simple to say, something useful to everybody, a film that could help bury forever all those dead things we carry within ourselves”. The passage reflects the existential crisis at the heart of the film, where Guido feels he needs to construct a better version of his life on screen to help erase the messy real one he’s living. When Guido is accused of exactly that he retreats into a nihilistic denial, “There’s no film, there’s nothing anywhere”, before he dreams of putting a gun to his own head. Fellini was talked out of a pessimistic ending based on a suicide and instead he opted for a leftover sequence of all the players gathering at the spaceship set and joining hands, its here where Carla tells him, “I understand, that you can’t do without us”. Once again connection is all.

Fellini uses his prodigious imagination in several bravura sequences and can be see as the natural link between the surreal 1930’s cinema of Jean Cocteau and Luis Buñuel and the modern genre of Magical Realism. The film contains delicate, original and inventive visuals, from the jaw dropping opening where Guido unexpectedly escapes a Roman traffic snarl, to the iconic imagery of Guido putting down a distaff rebellion as a lion tamer. With 8 ½ Fellini moved further away from the Neo-realism of his roots to a more ambiguous and adventurous visual style, one that allowed him to explore the idea of urban alienation in modern life, in much the same way (though not as bleakly) as his countryman and contemporary Michelangelo Antonioni.

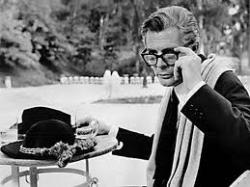

8 ½ is also a ferocious self examination by an artist in crisis, and of a husband who is less than ideal. The critic Daumier sums it up when he says to Guido, “What a monstrous presumption to think that others might enjoy the squalid catalogue of your mistakes”. Fellini initially wanted to cast Charlie Chaplin in the lead, before musing on Laurence Olivier, but the thought of working with such a well trained classical actor seems to have scared Fellini off, and he settled on Mastroianni as being his on screen embodiment, dressed in Fellini’s trademark black hat. Marital troubles with his actress wife forbade a role for her, although he subsequently created his next film specifically to work with her again.

8 ½ represented a kind of fin de siecle for Fellini, a last goodbye to any pretence at realism of any kind, neo or other, an unsurpassed achievement and a one-of-a-kind marker on his amazing cinematic sojourn. It was also an indicator for a broader palette with which Fellini would work, and in a way his career can be divided into films prior and post this masterpiece. The initial impact on the public was variable, but its effect on other artists was immediate, Roman Polanski said at the time, “It smote me like a revelation. It was all I’d ever dreamed of seeing on the screen, both emotionally and visually”. Fellini’s exploration of a Jungian ‘dream’ life in cinema would take up much of his subsequent career, and such a part of his signature style that the adjective ‘Fellini-esque’ entered common usage. 8 ½ would also be his last feature in black and white, which elegantly frames the stylish vignettes of Guido and his woman, but from his next feature, Juliet of the Spirits, starring his incomparable wife Guiletta Masina, he employed riotous colour schemes to bring his ‘dream’ cinema to life. 8 ½ is a personal and heartfelt daydream of a movie, rendered universal and sublime by the hand of a genius.