Altman does neo-noir

By Michael Roberts

"Words don't tell you what people are thinking. Rarely do we use words to really tell. We use words to sell people or to convince people or to make them admire us. It's all disguise. It's all hidden -- a secret language." ~ Robert Altman

Robert Altman was of a generation prior to the movie-brat group that revitalised the American film industry in the late 1960s and '70s, but his philosophy and métier perfectly fit the new mood of quasi-deconstructionist revisionism and he. more than any other, produced a body of work during that period that is the exemplar of imagination, daring and zest. Leigh Brackett adapted Raymond Chandler’s final novel The Long Goodbye as she’d helped to do with his The Big Sleep nearly 20 years before, and Altman only came to direct after Peter Bogdanovich turned it down, and in turn recommended it to Altman. Altman also only agreed to do it if Brackett’s ending remained unchanged, a far more cynical ending than the book had, which allowed him to make a far more effective payoff for what is a leisurely paced build.

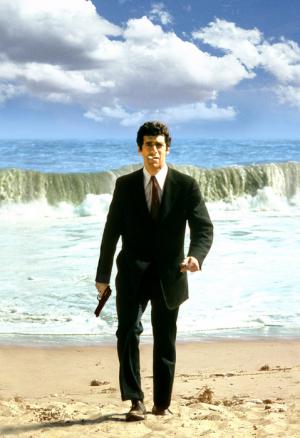

Altman makes it plain from the outset that he at once has an affection for the old Hollywood, and a certain contempt for it as well. Hooray for Hollywood plays over the opening titles which then makes way for a bravura ten minute riff on Philip Marlowe (Elliot Gould) attempting to feed his very fussy cat at 3AM. The scene is reminiscent of Paul Newman’s opening to the 1965 detective film Harper and indicates an allegiance to an oblique aesthetic in this Marlowe, rather than the directness of Bogart’s Marlowe, who wouldn’t have had a cat in the first place let alone attempt to outfox it with inferior food. Altman avoids a voiceover narration device by simply having Marlowe talk to himself in his mumbling sub-Brando tones, and this enables us to connect with the characters thoughts, even the inane and innocuous, as we get to know this laconic loser. The mood is also established of a ‘man out of time’, this Marlowe wears a dark suit when everyone else wears contemporary clothes, he’s the only one who smokes, he is in every way a man apart.

Marlowe is visited in the middle of the night by his friend Terry, who is in trouble and asks Marlowe to drive him to Mexico, which he does. On Marlowe’s return he finds the police waiting who inform him that Terry is wanted for the murder of his wife, and that makes Marlowe an accessory. Altman takes the opportunity to subvert the genre during the traditional police interrogation scene, and has Marlowe put on a ‘blackface’, at once compromising the integrity of the process and also making a subtle political point about who is usually the victim of these police tactics. Marlowe is released from the lock-up on the news that Terry has been found dead in Mexico as a suicide, but Marlowe doesn’t believe it. Marlowe takes a job from Eileen Wade (Nina Van Pallandt), a near neighbour of Terry’s at a rich Malibu beach side address, and soon both cases are intersecting. Marlowe tracks down missing husband Roger (Sterling Hayden) at a private hospital run by a sleazy Doctor (Henry Gibson) and brings him home to Eileen. The Wade’s marriage is obviously on the rocks and Marlowe catches some small inferences that Eileen knew more about Terry and his dead wife than she’s letting on. The sting in the tail is a vicious Jewish gangster called Augustine (Mark Rydell) claims Terry stole $350k from him and he pressures Marlowe to find it or suffer some drastic consequences. The trail leads Marlowe to Mexico and a confrontation with the truth.

Altman fills this California neo-noir dreamscape with all kinds of misfits and miscreants that manage to create a quotient of unease, an environment where Marlowe is never particularly comfortable or on top of the situation. His neighbours at the apartment block are a group of hippie, barely clad, pot head girls, doing their yoga and avoiding the ‘real’ world as much as possible, in their own way as disconnected as Marlowe. The gangster is a Hollywood Jew, a telling comment of Altman’s opinion of the industry, and also enabling him to bring some nasty violence into the action in an unexpected and sobering way, telling the audience and Marlowe as well ‘wake up, this is no hippie reverie’. Marlowe is called to action, his out of date apparel and choice of car (a vintage 1948 model) now serving as armour and steed as he charges into the fray. Another man out of time is Roger Wade, and Hayden gives a brilliant performance as the disheveled and alcoholic Hemingway-esque writer, who’s presence and gravitas further emphasises the ‘phony’ world of the Malibu rich that he’s obviously sold his artistic soul to, a world his wife is attached to. Wade is suffering writer’s block, or impotence in relation to his pretty wife, who needed to go elsewhere to get her sexual needs taken care of.

Altman’s soundtrack for much of the film is the churning and endless Malibu surf, reminding us of the constant impermanence of life, and also the John Williams and Johnny Mercer composed title song which is cleverly rendered in every genre imaginable from supermarket muzak, to Mexican funeral song! If Hawk’s The Big Sleep was a classic standard song, it would be a Sinatra record, timeless and solid, whereas Altman has delivered a film that approximates a John Coltrane free-form improvisation, fluid, mercurial and unpredictable.

"Jazz has endured because it doesn't have a beginning or an ending. It's a moment." ~ Robert Altman

Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, who has filmed the remarkable McCabe and Mrs Miller for Altman, shot the film with a washed out ambience that reflected the hazy disconnect of the culture, this haze that Marlowe eventually emerges from in the strongest possible terms to enact the bracing finale. Altman’s homage to the detective genre comes full circle as Hooray for Hollywood strikes up again, to accompany Gould’s now liberated Marlowe, a man who’s rediscovered his core, who’s gone through the trial to find his own throwback beating tempo is several notches higher than the laid back ’70s one he’d been living.

Gould’s stoner era laconic attitude works fine with the approach Altman takes and Gould makes the role his own, and considering the studio wanted either Robert Mitchum or Lee Marvin it’s a tribute to Altman’s vision that he backed Gould to do the lead. Rydell is a standout as the edgy Jewish gangster, and Van Pallandt hit the right tone as the ambiguous Eileen. Altman continued his explorations of various genres, and never spent too much time on any one in particular, and The Long Goodbye remained his only neo-noir. He dedicated the film to the actor Dan Blocker, who’d played ‘Hoss’ in the TV show Bonanza and who Altman had originally cast as Roger Wade, but who died just prior to production. Altman worked on Bonanza as well as many other TV shows before establishing his feature film reputation and becoming one of the pre-eminent directors in American cinema history.