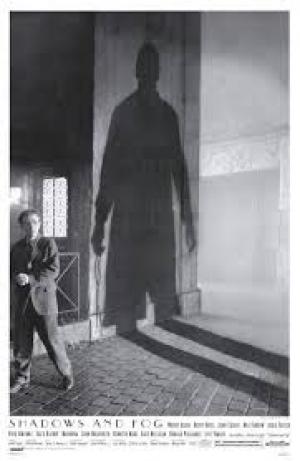

Woody goes Wiemar

By Michael Roberts

Woody Allen had already carved himself a unique notch as a comic observer of the neurotic side of human nature, a persona that served him well during his ‘early, funny’ phase. A tribute to the scope of his reach, and an acknowledgement of his unexpected love of art house cinema surfaced in the late ‘70’s when he got ‘serious’, with adult dramas such as Manhattan and Interiors particularly. Since then Allen has tended to vary his output by producing a mix of comedies and more serious tomes, and occasionally (given it’s Woody) combining those in the same film, and so it is with his smart homage to German Expressionism, Shadows and Fog.

A murderer is at work in an old part of an unidentified European city in a non defined period, possibly the 1930’s. Kleinman (Woody Allen) is roused from his sleep by a vigilante mob and pressed into helping find the murderer. A circus troupe performs on the outskirts of the city, and two of its members, Irmy (Mia Farrow) and Paul (John Malkovich) have an argument over children, causing Irmy to walk out. Irmy finds shelter with prostitutes in a whorehouse, and while there she is propositioned by a student regular named Jack (John Cusack). Paul walks the streets of the city looking for Irmy, who finds friendship with Kleinman after leaving the whorehouse. Soon the mob is accusing Kleinman and the real killer is still on the loose.

Woody again uses his default ‘fraidy cat’ character for Kleinman, the one recognisably (and admittedly) directly descended from Bob Hope’s stock screen persona. Woody avoids the broader and more surreal observations of his earlier work in favour of a light hearted existentialist debate to tongue-in-cheekly uncover “something definitive about the nature of evil”. The ensemble cast includes comic and tragic characters, who weave in and out of the narrative and allow some excellent Allen riffs on existentialism, God and the nature of love. The shadowy world of the streets and the underlying fear in the darkness also let’s Woody ponder the nature of mobs, and as such the entire piece is a comment on the rise of fascism in Europe post WWI. The Church here is complicit with the mob, which represents the state, making lists and taking names, and Kleinman discover citizens under suspicion can be removed for a price.

Irmy and the circus folk are outsiders, fringe dwellers who provide escapism for the masses, but they are also people looking for everything ‘normal’ people desire. Woody uses them to contrast with the earthy concerns of the prostitutes, also outsiders, and the intellectual musings of the students. Kleinman debates Jack about the existence of God, a device that places Allen in the territory of his idol Ingmar Bergman, and the relative merit of “better false Gods than no God at all”. Woody opts for a black and white visual mood, and his cinematographer, and Antonioni alumni, Carlo Di Palma has great fun in approximating Lang, Murnau and the tones of the Weimar Expressionists. Woody adds to the party by using the music of Kurt Weil on the soundtrack, which incredibly is suitably sinister and jocular in equal parts.

Woody’s Kleinman exists in a Kafkaesque nightmare, trying to divine what exactly “the plan” is that the angry mob seems to be following. Kleinman bounces from fear of the killer to fear of the mob, and all are in terror of the monster from the Id. The mob voice Old Testament concepts of guilt, “We did something to deserve this”, as they demand to know “Are you with us or against us”? In Woody’s universe science is impotent (the Doctor is murdered) the Church is ineffectual and corrupt, real life and empathy is found amongst the outcasts and marginalised and only love (in all of its glorious unknowable-ness) survives. Woody ends on a quasi-magical note involving the circus magician, an almost solipsistic denouement as he declares “Illusions? They love them; they need them like they need the air”.

Allen stacks the cast with a wide range of character actors, and all get the opportunity to make an impression. Donald Pleasence is wonderful as the slightly addled Doctor, Julie Kavner shines as Kleinman’s ex-girlfriend and Kathy Bates, Lily Tomlin and Jodie Foster make a fine trio of earthy hookers. The narrative hinges on Irmy’s hope for love and fulfilment and Mia Farrow delivers a delicately layered performance as the much put upon sword swallower, matched by a typically muscular John Malkovich turn as Paul. John Cusack chimes in nicely with his earnest student, and Woody plays Woody as only Woody can.

Shadows and Fog confounded both critics and public alike, even though Woody had been defying expectations for years by the time of its release. It is at once a gentle satire on existentialist tropes, and a warm hearted affirmation of the desire to understand the human condition. Woody succeeded in making an homage to the art film, and wisely did not attempt to inhabit the same esoteric territory of the giants of existentialist cinema, and anyone who takes this film too seriously has missed the point. Woody’s funny bone forces him to find humour in most situations, even the rise of European fascism, and given his penchant for whimsy and even (gasp!) irony, his sometimes gentle observations can sometimes leave the mainstream viewer bemused, bothered and bewildered. But when he gets it right it’s delightful, and humour is very many times the best weapon we have against, and aid to understanding the darkness within.

Shadows and Fog, a clear winner.