East goes west

By Michael Roberts

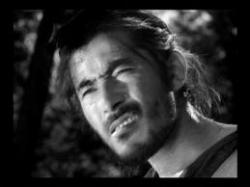

Akira Kurosawa insinuated himself indelibly into the sensibilities of world cinemagoers with his remarkable moral fable 'Rashomon' in 1950. Japan had done itself no favours in the opinion of the rest of the planet with it's behaviour in WWII and artists like Kurosawa reminded us that Japan wasn't just about feudal and archaic militarism, but represented a civilisation and a humanity that stretched back thousands of years. In 'Rashomon' Kurosawa looks at the nature of truth, a dissection of perspective and bias in light of the evidence of our eyes, and challenges our ability to make judgements based on what we know as opposed to what we feel. The film marked the first of three significant collaborations with Japanese cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, and his contribution complimented Kurosawa's vision perfectly to create a bold and effective visual language. Kurosawa's other key collaborator was actor Toshiro Mifune, who had worked on two notable films for Kurosawa after the war, 'Drunken Angel' and 'Stray Dog'. Mifune was the perfect Kurosawa muse in many ways, and together they made sixteen films.

Kurosawa opens with pouring rain and a dilapidated temple, where two men, a Priest and a Woodcutter meet and begin to discuss a "strange story". The context is a medieval period encompassing plague, devastation and war, and yet this one event seems more troubling to the Priest who says, "This time I may finally lose my faith in the human soul". A third man, a Commoner joins the pair, seeking shelter and warmth, and listens as the two men tell what they know. The story involves the killing of an upper class Samurai, but by whose hand becomes increasingly uncertain as different perspectives of the same event are related. The Woodcutter tells what appears to be an unbiased account, as he observed the incident, having found the body of the dead man and reported it to the authorities. At the trial, we hear a bandit's testimony, as Tajōmaru (Toshiro Mifune) recounts his side of the tale, before the woman (Machiko Kyō) gives her summation, which contradicts the bandits. A medium gives the dead man's perspective, and the Woodcutter gives his trial account last, leaving the truth uncertain and subjective at best. Ultimately, the Commoner is unsure who did what to whom, but the trio finds a baby abandoned at the temple and the Woodcutter offers to care for it, restoring the Priests faith in humanity.

The strength of Kurosawa's approach is to highlight the ambiguity of nature and the unreliability of 'eyewitness' testimony. Kurosawa reminds us that a human being is a flawed information delivery mechanism, prone to bias and selectivity, and any information needs to seen through that prism. "It's human to lie", is how he succinctly states it, underlining his choices metaphysically by use of rain and sunshine for contrast. The added dimension of a plague ravaged land, where "men are killed by insects", provides another layer of mystical interpretation to man's actions. The Priest comments that, "a human life is truly as frail and fleeting as the morning dew", and seeks the deeper meaning in the actions of the people involved. Kurosawa is saying in effect, 'there is no deeper meaning, just the actions and facts, and even then we will struggle to understand it'. Kurosawa is relentlessly unsentimental in his examination of the human heart, "I don't care if it's a lie, as long as it's entertaining", says the Commoner. This directness allows the denouement to feel real, and not emotionally manipulative, as nothing Kurosawa has offered in the lead up has had any degree of saccharine sweetness to it. Jean Renoir proffered that 'everyone has their reasons', and it's plain Kurosawa agrees.

Kurosawa worked with a small crew, living together and working out the intricacies of the complex set up, and the results are evident in the final product. Miyagawa's stunning and fluid camerawork and the intense lighting scheme provide a superb visual palette, and one that broke new ground in some areas. Miyagawa shot directly into the sun, in absolute contravention of accepted cinematographic practices, and enhanced the intensity of the lighting in the dense forest with reflective mirrors to create a dappled chiaroscuro. The pouring rain that is so much a part of the oppressive visual atmosphere at the temple was made possible by adding black ink to the water mix to make it show up better on film. Miyagawa used elaborate tracking shots through the forest when following the woodcutter, weaving his camera around the character and giving an added feeling for the environment. These innovative and imaginative ideas all reveal a high degree of artistry and a fertile partnership at work.

'Rashomon' is a poetic and powerful dissection of the human heart and all it's vagaries and foibles, where a man is at the mercy of a zephyr's caprice that lifts a woman's veil for a split second and brings a brigand undone. Kurosawa understands that these fleeting moments of chance are a microcosm of the human experience, where we all live random sequential moments of chance from an uncertain start to an unknowable finish. 'Rashomon' was Kurosawa's calling card to the western world, where soon his name became a by-word for master director, and his subsequent output only added to the legend of a cinematic genius.