From le petite mort to la grand sommeil?

By Michael Roberts

“One lives one’s death, one dies one’s life” – Jean Paul Satre

Louis Malle came to create one of his greatest films, and his existentialist masterpiece in 1963, after his assured debut and controversial sophomore efforts had marked him as a major new cinematic talent. The stunning Ascenseur pour l'échafaud and Les Amants in 1958, coincided with the beginnings of the Nouvelle Vague, and Malle appeared to get their blessing after Truffaut sent him a ‘fan’ letter praising Malle’s third film, the quirky and offbeat Zazie dans le Metro. Malle then succumbed to the temptation of casting the hottest star of the time, Bridgette Bardot, in his next film, the overblown and relatively unsuccessful Vie Privée. Malle chose to follow this populist flop with a film that was as far away from the soft May-December romance of the Bardot and Marcello Mastroianni piece, the sombre and serious Le Feu Follet. Malle changed cinematographers, forsaking regular collaborator and French New Wave icon Henri Decae for Ghislain Cloquet, and applied a ‘realist’ manifesto to shooting. Malle also incorporated some of his earlier influences, firstly those as a documentary maker, where he’d won an Academy Award with Jacques Costeau for The Silent World, and secondly a minimalist aesthetic from his time as assistant director on the Bresson masterpiece A Man Escaped.

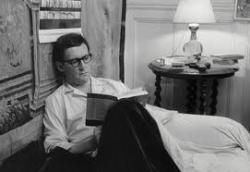

A man and a woman are making love, before it becomes clear that he is a patient in a mental health clinic and she is a visitor. Alain (Maurice Ronet) is estranged from his wife, who lives in New York, and the woman is a friend of his wife’s who is visiting him in Versailles to report back on his progress. Alain seems to have shrugged off the depression that the separation has engendered, superficially at least, and he begins to take steps in re-examining a life on the outside. Alain visits an old friend and ex comrade, Dubourg (Bernard Noel) a former roué like himself, but who has since ceased his wild living and settled into domestic bliss with a wife and two children, contentedly writing academic tracts on Egyptology. Alain reveals his true emotional condition to Dubourg, “I wanted you to help me die”, he says by way of explanation. Alain continues to visit the old haunts, attempting to recapture something of his past, as he reconciles his present and ponders a future that seems out of reach. Alain successfully leaves us guessing as to his decision, as life appears to offer him possibilities that others would envy, and this underlines the difficulty of walking in anothers shoes.

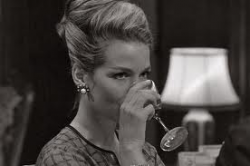

Alain’s opening confessions to his lover are a clue to his state of mind, saying that “feeling has eluded me”, and later concluding “when I touch things I feel nothing”. Alain is dividing the world into the immanent and corporeal, and contemplating the lack of the transcendent in his life. Alain’s Doctor voices platitudes about his improvements, blithely missing a key statement from Alain, “I’ll be gone by the end of the week, come what may”, as he routinely tells him “life is good”. Alain rejoinder is “good for what”? Alain tells his now bourgeois friend Dubourg, that a life of “gilded mediocrity” holds no attraction for him, as he paradoxically envies his friend and despises him. The arc of the journey for Alain cleverly examines the prospect of happiness in differing class levels; the working class via truck drivers and a bartender, the middle class via Dubourg, the arty clique of Jeanne (Jeanne Moreau) and his rich friends, Levaud (Jacques Sereys) and his beautiful wife Solange (Alexandra Stewart).

Malle obliquely addresses the great political issue of the time in France, the Algerian conflict, in as much as Alain and Dubourg are ex vets, and he hints that Alain has a kind of post traumatic stress syndrome. “The war is over” he’s told, as he hears of the troubled exploits of his former Army colleagues having difficulty adjusting to the pace of civilian life. The alcoholism that Alain battles is also not overplayed, as Malle lays bare a life as the sum of the parts of a man, vainly trying to add it up into a coherent whole. Alain confronts the decadence of an opium den, possibly measuring it against the misery he experienced in Algeria, or the pain and confusion of the lack of any emotional connection.

The film can also be read as a comment on the unresolved tension between ‘le petite mort’, the French concept of the sexual climax, and ‘le grand sommeil’, the ‘big sleep’ or death. Alain associates women with ‘life’, and regrets he does not have access to that association, to “things well done”, all he feels is the emptiness and lack of the ‘other’. Alain has a chequered history with the women in his life, and it’s clear they all adore him, but even their spark cannot ignite his ‘fire within’. He sees his past in a younger version of himself, and equally sees the lack of a meaningful future. Alain is greeted as a ‘revenant’ by his wealthy friends, who idolise a pretentious intellectual at the dinner party that he attends, but Alain is the outsider, unable to relate.

It is in this context that Alain must confront the great existentialist question, as posed by Albert Camus “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts toanswering the fundamental question of philosophy.” Alain examines his own life and makes his choice, deciding if he goes through with it he will leave his wife with “an indelible stain”. It's a telling fact that even with the fiercely Catholic background of France that the notion of committing a 'cardinal sin' doesn't get any airing, it's refreshing to see the morality of the act remaining uncontroversial in the context of the film. Ultimately, it’s up to every individual to decide upon the moral worth of their own life, and to give it shape and meaning, as for humans the realisation of the inevitability of our own death layers on a dimension of exquisite yet bittersweet sadness.

Maurice Ronet, who starred along with Moreau in Malle’s stunning debut feature, plays Alain with a minimalist delicacy, recalling the best of Robert Bresson’s ‘models’. Bresson employed Malle as an assistant on his masterful A Man Escaped, and the lessons learned are readily apparent in the stripped back visual aesthetic. Malle also employs his documentary maker’s eye in the vibrant street scenes of Paris, as the lively and bustling populus contrasts with Alain’s lonely quest. The soundtrack is also Bressionian in Malle’s use of the evocative and spare piano pieces of Erik Satie, a perfect haunting aural foil to the melancholic reverie.

Malle seemed to pursue tangential projects with more vigour than his contemporaries, and did not assiduously direct the arc of his career as other’s by developing a signature trope or style. Malle turned 360 degrees from the gravitas of Le Feu Follet to the lightweight and frivolous for his next two features, Viva Maria, with Bardot and Moreau, and The Thief of Paris with screen icon Jean Paul Belmondo. Malle then abandoned feature films to return to documentary making with his cycle on India in the late '60's. Malle, like many other western Europeans, joined the ‘hippie trail’ in the wake of The Beatles promoting of Indian values via the Maharishi, and coincidentally later married Transcendental Meditation devotee Candice Bergen.

It’s possibly because his output was not easily categorised, and that he was never pinned down into an easily digestible sound bite that Malle didn’t enjoy the reputation of his peers like Truffaut and Godard, but his work stands with the best of the modern French directors. Le Feu Follet is a masterpiece, one of the greatest French films of the ‘60’s, and in an era full of superb cinematic gems this one shines like few others. It is a raw and heartfelt essay on the value of life, reaffirming the existentialist ethos that it’s only knowing we will die that allows us the opportunity to invest our life with meaning. Masterful Malle.

“Let us beware of saying that death is the opposite of life. The living being is only a species of the dead, and a very rare species.” - Friedrich Nietzsche