Collective masterpiece

By Michael Roberts

'Real life is ugly, but we can't make good pictures until we're ready to tell about it.' ~ Robert Rossen

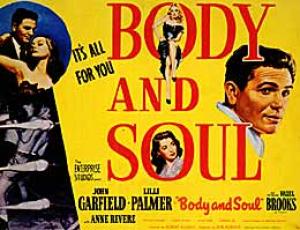

Body and Soul is one of the richest cinematic experiences in the Film Noir genre, and rather than being seen as the director’s auteurist vision it should be seen as a masterpiece of collective effort, in the same way Casablanca is, only in this case it may be more ironically appropriate, given the communist and leftist connections involved. The producer-star, director and writer had all come through left-leaning New York theatre groups during the 1930s, a period when hundreds of thousands of Americans were members of the Communist Party or Leftist organisations. John Garfield had formed Enterprise Productions with a former business manager, Bob Roberts and this was their most successful project, Garfield attracted initially by a script based on the career of a Jewish boxer Barney Ross. After some fuss was made about the fact Ross became a drug addict the film was cancelled, but the slated director Rossen threatened to sue and it went ahead with all mentions of Barney Ross removed. Polonsky got the job from Arnold Manoff who had quit and mentioned Polonsky to Garfield after a meeting at Paramount. Garfield said send him over and Polonsky sketched out the plot in the 2 block walk to cover the lie that Manoff had told that he already had an outline. Abraham Polonsky’s script is concerned with the corrupting power of money, and if capitalism invokes a mantra of ‘money at all cost’ then it should be condemned, and this philosophy led to Body and Soul coming to the attention of the HUAC Standing Committee investigations in the early 1950s, resulting in the blacklisting of all three main contributors.

Charley Davis (Garfield) wakes from a nightmare at his training camp prior to the big fight, only to find he’s still living one as he’s agreed to throw a mob controlled championship bout for the money. He returns to his mother’s city apartment and it’s clear they are estranged, and when his ex-girlfriend Peg (Lilli Palmer) walks in the tension is palpable. What has Charley done to alienate the most important people in his life is the question we investigate via flashback from here. We meet Charley years earlier, his face unscarred and fresh, as he first meets Peg, an artist with whom he becomes entranced. Her cultured and worldly independence is a rarity in Charley’s lower East-side world, and as opposites attract they become romantically involved. Charley’s friend Shorty (Joseph Pevney) is continually trying to advance Charley’s boxing career, a way out of the slums for both of them, and gets the slimy hustler Quinn (William Conrad) to intercede with big shot promoter Roberts (Lloyd Goff) to get Charley some choice fights. Charley’s mother hates the fight game and wants him to get an education but when his father is killed in a botched gangland hit Charley has no choice but to follow the money he can make with his fists. Charley works his way up on the circuit via a series of more high profile bouts and returns to Peg after a year, his face scarred and his bank account full. Roberts organises Charley’s title shot, not only not telling him it’s fixed for the champ Ben (Canada Lee) to lose, but that Ben has a blood clot and should not be fighting at all. When Roberts is challenged on this he replies with his favourite smartalec catchphrase ‘Everybody dies’.

Charley becomes champ, nearly killing Ben in the process, but taking him on as a trainer to help him live. Charley secretly cuts Shorty out of a slice of the action, continuing to pay him out of his own cut, as he gets deeper and deeper into the lifestyle of the World Champion. Gangster’s moll Alice (Hazel Brooks) sees Charley as the main chance and attempts to freeze Peg out of Charley’s affections, from distracting him at training by hugging the punching bag he’s hitting to sitting ringside at the title fight yelling ‘kill him Charley’. Shortey discovers he’s been frozen out of the deal by Roberts and tells Charley he ‘won foul’ in the title fight, and that ’you’re not a fighter, you’re money’. Peg warns Charley he gives up fighting or she leaves. Shortey is bashed by Roberts’ thugs and then accidentally killed and Charley takes up with Alice, living the high life and getting more in debt to Roberts. Eventually Charley becomes the hunted and a title fight is arranged with a new challenger and Roberts decides it’s Charley’s time to throw the fight, but making Charley a wealthy man in the process. During Charley’s return to his mother’s all the neighbourhood locals tell Charley they have their money on him, they believe in him, and with Peg reaching for the remaining scraps of humanity in Charley he starts to doubt his deal with the devil. At the training camp Ben’s injury finally takes his life and Charley finds out of his complicity in his death, still intending to throw the fight. As the fight unfolds he finally pulls himself out of his moral fog to stand up to Roberts and fight fair. In a titanic struggle where Charley takes a huge amount of punishment he wins, knowing it will mean losing all the money and that the mob will want him dead. He finds Peg and walks away from the stadium as Roberts confronts him asking him if he knows what he’s done? Charley replies ‘what are you going to do, kill me? everybody dies’!

Polansky’s script is razor sharp, and it beautifully points up the banality of evil in the Roberts character (the name surely an in-joke given the films producer) and the complicit acquiescence the corrupt system demands in order for it to function. Charley sells his ‘soul’ for money and fame to the mob, who own him ‘body and soul’, and only the decency of Peg’s love and the love of family can help him rise to a level of self-realisation and struggle back to find redemption, even if it costs his life. While Hazel Brooks plays the prototype Noir femme fatale it’s Palmer’s Peg that centres the piece, given her different style and sensibilities. Lilli Palmer was another German Jew who fled Hitler, via Paris and London, ending up in Hollywood with husband Rex Harrison, her European worldliness and delicate manner is a nice counterpoint to the lower East-side milieu. Garfield is commanding as Davis, a reminder of his range and stage training as an actor which added greatly to the performance. The unsung star of the show however is James Wong Howe, the brilliant Chinese born cameraman who shot the film so beautifully, from the opening crane shot in the training camp, to the cluttered noir world of the slums to the incredible fluid roller-skate shots of the boxing. Noted contributors also who went on to directing careers were assistant director Robert Aldrich and editor Robert Parrish.

The sad postscript to this film was the blacklisting of Rossen, Garfield and Polonsky. Rossen suffered blacklisting after his first appearance before HUAC where he took his Fifth Amendment right, he then appeared again after 2 years of not working and named names, including Jules Dassin. Polonsky, who had less to lose than Rossen who by then had won a Best Picture Academy Award, was an unfriendly witness and had to work under non-de-plumes until 1968 when Don Siegel credited him as writer on Madigan. Garfield was called and refused to name names, effectively ending his screen career. He returned to the stage and eventually wrote a newspaper piece condemning Communism, ironically his wife was a member of the party and the problems this caused, along with the stress of the HUAC on-going investigation contributed to his early death from a heart attack at age 39. Body and Soul is a fine legacy to a great actor and liberal thinker who produced this cautionary fable on greed, one assumes he would have agreed with Bob Dylan’s pithy summation some years later that ‘money doesn’t talk, it swears’!.