A Streetcar (cable car?) named Jasmine, a tale of two sisters.

By Michael Roberts

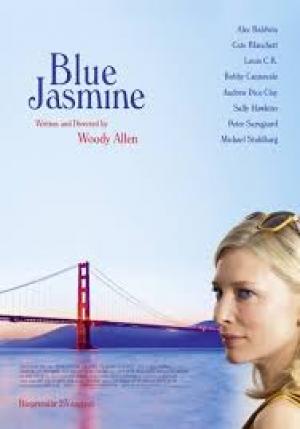

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, for Jasmine at least. Woody Allen, however, continues to enjoy the best of times after his late career form took a turn for the better with the superior Midnight in Paris, and carried on with projects worthy of his idiosyncratic gifts, until he’s again struck paydirt with Blue Jasmine. Allen boldly cast non-American theatre trained actors in the key roles of the ‘chalk and cheese’, adopted sisters, in Cate Blanchett and Sally Hawkins, and the move pays off in spades as the talented women give voice to Woody’s bittersweet words. Woody is seemingly paying homage to Tennessee Williams’ iconic play A Streetcar Named Desire, which is no back-handed compliment as the work stands on its own, but it’s no coincidence, we assume, that he chose Blanchett, who’d had a triumph as Blanche Du Bois on the Sydney stage in 2008.

Jeanette ‘Jasmine’ (Cate Blanchett) catches a flight from New York to San Francisco to stay with her sister, Ginger (Sally Hawkins). Jasmine needs somewhere to stay and in a series of inter-cut flashbacks we learn the reason why. Jasmine has enjoyed a life of privileged wealth on the East coast since her marriage to financial ‘wizard’ Hal (Alec Baldwin). Hal was arrested for illegal business practices that left investors penniless, including Ginger and husband Augie (Andrew Dice Clay), and later hanged himself in prison. The sisters share a modest apartment, with Ginger’s two young sons, and struggle to re-connect in a meaningful way as they both try to carve a future that fits. Both women face issues with each other, and issues with men as they increasingly lean on the other, finding they have more in common than is obvious.

Jasmine’s fall from grace is beautifully handled by the ensemble, as the dimensions of the change in circumstances sinks in, challenging Jasmine’s fragile mental state. If Jasmine has not “always relied on the kindness of strangers”, she certainly needs to now, and Woody has the working class types from Ginger’s orbit treat Jasmine with simple decency. Ginger is a stranger to Jasmine in many ways, and Woody throws in the disorienting fact they were both adopted, and so are not blood relatives at all, a neat reminder that human connection is not a neat equation. Jasmine struggles to assimilate the new environment into her ‘great’ expectations, and ultimately falls back on the only thing she knows, using her mystique and allure to ensnare a rich man. At Jasmine’s urging Ginger too rethinks her relationship and penchant for rough but honest men, hooking up with a man who seems kind and sweet, saying “I never had a sweet guy”. Ginger finds out that surface impressions are shallow, that real commitment requires work, and that depth can be found in surprising places.

Woody is not a writer given to examining the political, at least not overtly, and Blue Jasmine does not break his streak, even though the opportunity presented itself given Hal’s business. One of the great furphy’s in America is that it is a classless society, when in fact class is carved deep into their culture, mostly because of relative levels of affluence, and the resultant impact that has on opportunity. Woody sets his parameters, upper Manhattan and lower San Francisco, and cannot help but obliquely comment on the class divide between Jasmine and Ginger. Ginger and Augie are bound by the restrictions of the working class, until a windfall lottery win gives the couple a chance to break the cycle, and to start their own business. “You’ve got tohave money to make money”, Ginger tells Augie, not realising that operators like Hal add the tacit words “other peoples”, in front of the first ‘money’.

The film simply turns on Blanchett’s razor sharp characterisation of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Blanchett exudes authority at every level of her performance, able to convey delicacy in the quite moments of torment, and verve in the flashier, upper class and superficial world of the East Coast elites. Jasmine is tortured by the reduced social circumstance she finds herself in, and maintains the forlorn hope she can drag herself out of it and achieve “something substantial”. Reality sets in, a detour via a dentist turns out badly and she finally realises the only thing her life has qualified her for is interior design in dressing rich peoples rooms, in creating pretty facades, illusions. When troubled waters arise and some of her lies come back to haunt her she cries, “My feeling, my ideas, my humour, isn’t that who I am”?! Jasmine, to her horror, finds intelligence, beauty and style is not enough, there is something to be said for perseverance and grit, something the working class Ginger possesses in spades. Sally Hawkins is superb as Ginger, and provides a crucial sounding board for Blanchett while creating a memorable character in her own right, and Andrew Dice Clay is a revelation as a serious actor.

The abandonment of Jasmine by her rich and superficial friends is underscored by the support and humour she finds amongst Ginger’s friends, who put aside their suspicions of her complicity in Augie’s disastrous investment attempt, and try to engage her in their activities. Jasmine faces her preconceptions, but finally does not have the tools to connect as the psychological damage from her previous life creeps up on her. Hal’s empire was illusory, and Jasmine closed herself off to any questions that his gains were ill-gotten. Ultimately she admits, “You’d have to have been an idiot not to know”, leaving hanging the implications for the Madison Avenue types still guarding the buried bodies of failed, Bernie Madoff type, financial schemes.

Woody employs a signature soundtrack of old tunes that evoke times long gone, and Jasmine’s theme is the old standard Blue Moon. As Jasmine spirals into a ‘blue’ mood, she tries to recall the pivotal tune that played when she fell in love with Hal, “I used to know the words.. ah…. all a jumble…” It’s a heartbreaking coda at the end of a bittersweet quintet piece. This is one of the rare times that the woman character in an Allen film takes on some of the neurotic foibles that Woody normally assigns to his male leads, often playing the parts himself. Woody, for all his ability as the finest chronicler of his own personal, urban neuroses, has consistently proved himself one the finest writers for women in modern cinema, and this flm is the crowning glory of that side of his work. Blue Jasmine, if not a wholly satisfying film, is elevated to the more memorable of Woody’s concoctions by a withering performance from Cate Blanchett, which is nothing short of stellar, stelllaarr!! Stellllaaarrr!!!