Walsh gets nostalgic

By Robert Regan

"They called me the one-eyed bandit. And why not? I sure gave Hollywood one helluva run for its money." ~ Raoul Walsh

The device of presenting the opening credits of a film on the turning pages of a book has generally been an attempt to emphasize a respectable literary pedigree or to assert an affinity to a well-known best seller. The effect is quite different when Raoul Walsh begins his Gentleman Jim or Wild Girl with an old-fashioned family photograph album. These albums open to reveal a deeply personal vision of the past; in them Walsh (born in 1897) reconstructs the world of his childhood years with the same poetic grace with which Jean Renoir lovingly looked back on the days of his father's youth in Partie de campagne, French Cancan, or Elena et les hommes.

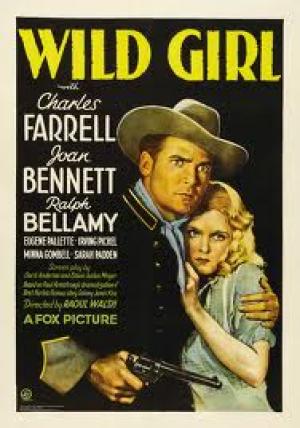

As Wild Girl fades in, Walsh draws us gently into his fantasy by moving his camera closer to the album before its cover opens to three pages of credits and nine pages of talking portraits of the principal characters who introduce and briefly characterize themselves, as when young blonde Joan Bennett tells us, "I'm Salomy Jane. I like trees better'n men--they're straight." Throughout the first half of the film, Walsh punctuates his narrative by turning the entire image over to the left, repeating the album motif. In this way, he structures his exposition while reminding us of his nostalgic intentions. As the tempo of the narrative increases, the device is abandoned until the film's last few minutes to prepare us for the inevitable closing of the album cover and the final fade-out.

If Wild Girl is ranked somewhat below Walsh's best work, for example the similarly warm and sentimental Gentleman Jim, it is because he at times allows his script's theatrical origin to remain a bit too obvious, particularly when Eugene Pallette as the stagecoach driver keeps turning up in the local saloon to deliver, like a Greek messenger, a long speech describing critical off-screen action. Even this apparent failing, though, contributes to the tenderness of Walsh's journey into the past. Paul Armstrong (1869-1915), the dramatizer of Bret Harte's Salomy Jane's Kiss, was a close friend of the Walsh family and young Raoul's most important mentor until his association with D.W. Griffith.

Neither these briefly static passages, nor the occasionally heavy stage melodrama conventions of Wild Girl's plot, overshadow the shimmering beauty of California's Sequoia forest, photographed by Norbert Brodine, the pioneer cinematographer who also shot Walsh's next film, Me and My Gal. In this enchanted forest, Salomy and The Stranger (Charles Farrell) find the freedom and the peace that Humphrey Bogart as Roy Earle was to seek with less success in Walsh's later High Sierra.