So it goes

By Michael Roberts

"Here we are, trapped in the amber of the moment. There is no why." ~ Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

Kurt Vonnegut's individualistic, elusive and allusive way with prose should have meant his classic novel Slaughterhouse Five or the Children's Crusade should have been next to unfilmable, set as it was in three different time eras just to complicate things. George Roy Hill, who had no track record with science fiction, and like Robert Altman a background in TV, was given the job by Universal to bring it to the screen and did such a good job that Vonnegut famously said, 'only two author's have reason to be grateful to the American motion picture business, Margaret Mitchell and me'. Hill captures the essence of the novel's understated whimsy and peerless satire, focusing its spotlight on the core issue of man's inhumanity to man. As much of the film was shot in Prague, standing in for Dresden, Hill employed Miroslav Ondricek as the cinematographer, a veteran of shoots for both Milos Forman and Lindsay Anderson. The detail in the set design and the staging is superb, Hill might easily have been helming a big budget war movie as was popular at the time, instead the devasting scenes of war are but a part of a much more complex fabric woven around the life of an innocent everyman, Billy Pilgrim.

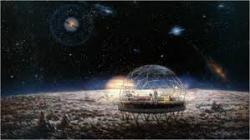

Billy (Michael Sacks) is writing as letter, 'I've become unstuck in time', as we discover his ability to roam backwards and forward between different periods of his life he his suddenly a young man in Germany in WWII. Assistant Chaplain Pilgrim finds himself in a snow covered foxhole with the psychotic grunt Paul Lazzaro (Ron Leibman), and the pair are soon captured and sent to a prison compound in Dresden, an old abattoir, Slaughterhouse-Five. Billy roams between that period and the day of his wedding to Valencia (Sharon Gans), the daughter of an Optometrist, Billy's chosen profession, where she promises to lose weight for him, she never does. Billy's return from the war led to a nervous breakdown, where he was treated with Electroshock Therapy, and retreated from the world, preferring the company of his dog. Billy develops a quiet fixation on nude centrefold model and soft-core porn film actress Montana Wildhack (Valerie Perrine), and after he's eventually transported to the Planet of Tralfamadore (with his dog!) it's her the aliens kidnap for him to spend eternity with. Eventually Billy, who sees his own death, goes through the motions of being assassinated by Lazzaro as he's a guest speaker on the nature of time, knowing that it is all cyclical and it will happen again, 'it has always happened that way, it will always happen that way'.

Vonnegut is commenting on the idea of predestination or predetermination, much loved by the Calvinists, where all events play out in a prearranged fashion, and therefore 'free will' is redundant. The Billy character is a Chaplain's assistant, and in a couple of instances his only recourse to action is to pray, made even more impotent in a pre-determinist philosophy, because that omnipotent God cannot change what he's set in motion. The Tralfamadorian's tell Billy they've 'Made a study of 31 different planets and only on earth is there any talk of free will'. Billy merely experiences his life in a non linear fashion, or 'a collection of moments'. Vonnegut paints on the large canvas, with the WWII bombing of a non military 'safe' town and the killing of tens of thousands of civilians, large scale inhumanity in an inhumane war, and also in the intimate moments where he drills right down to the execution of a single soldier for theft from the rubble of a tiny porcelain figurine. Vonnegut also indicates that Billy is disconnected in his own life, he can't relate to his suburban wife and her value system, and goes through the motion of being a 'normal' husband and father, but ultimately his dream life lies elsewhere, with his 'dream girl' cipher Montana, a satirical caricature, away from the suburban house that is as much a prison as his Dresden slaughterhouse ever was.

Billy's existentialist dilemma is making sense of the value of his life when it's so disjointed, and Vonnegut is testing our ideas of time by saying, 'if it's deconstructed like a Picasso painting and reassembled as a cubist collage, then does it make it any more meaningful'? The 'petty humiliations Billy finds at the hands of the Nazi's are compensated for by finding delicate human moments amidst the horror, such as the march through Dresden where a young German soldier shares a smile and a wave from a young Fraulein in an apartment. It's a beautiful 'grace note' that Hill finds to communicate the Vonnegut even handedness, beauty and madness on both sides, and later the soldier runs through the rubble to find the apartment building blown to bits. The decency of Edgar Derby (Eugene Roche) in the camp contrasts to the vile Lazzaro, as Billy finds a sympathetic friend to help cope with the horrors of incarceration. The Russians are dour and the British are jolly in arch stereotypes that deepen the satire and reveal the futility of entrenched human dogma, under the skin, stripped naked in a prisoner of war camp shower block, we're all the same. A biting moment has Derby rail at a buffoonish, traitorous American Campbell, who is recruiting for a super army after the war to help run a Nazi controlled USA, Lazarro enlists as the bombs start falling, the pathetic background being a German army reduced to recruiting old men and young boys.

The Dresden issue was problematical for Vonnegut, who lived through the event and didn't want to be seen profiting from it, but it's this crucial wartime experience in the city that informed his writing. He survived the bombing in a meat-locker and described the aftermath as 'carnage unfathomable', and helped the Germans pile their dead and burn the bodies in the streets with flamethrowers. The city was widely believed to be 'safe', Churchill's nephew was rumoured to be living there, consequently as a target of no military value it had no system of air raid shelters as a result the destruction and death were amplified. Widely interpreted as 'payback' for the Luftwaffe bombing of Coventry earlier in the war, it was also condemned at the time and in later years but the proponents of 'total war' on both sides would have no problem with the wholesale destruction of essentially civilian targets, but Vonnegut frames it for the madness it was, topping off the slaughter with a blackly ironic 'You can't trust the Jews' from Lazzaro. Vonnegut understood that if you have to become the monster in order to defeat the monster, then something is inevitably lost as a result.

George Roy Hill's handling of the material is able and confident, wringing all the nuances from Stephen Geller's witty script. The film contains moments of pathos and power, of epic brutality and intimate reveals, it's a tribute to Hill that he could connect all the moments so seamlessly, cutting them often between Billy's different time periods. There's a car sequence to make Steve McQueen's Bullit green with envy, ending as it does unexpectedly and sardonically. The music Hill uses is a particular highlight from Glenn Gould, the Canadian eccentric who scores by means of classical pieces, and it elevates the film to a kind of mythic timelessness which sits well with the tone. Strange to think this film, which was not a commercial hit but did well with critics, was sandwiched in Hill's filmography between the brilliant Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and the mega hit re-teaming of Redford and Newman in The Sting, the year following Slaughterhouse-Five. Vonnegut's superb writing is a thing of unique joy, but as far as making a film that captures some of its elliptical tone and charm, against all expectations George Roy Hill pulled it off. So it goes.