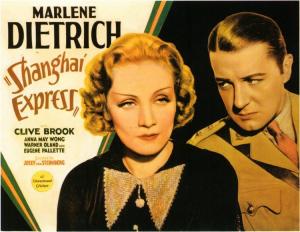

Jo's indelible faux east

By Michael Roberts

'In America, sex is an obsession, in other parts of the world it's a fact.' ~ Marlene Dietrich

After the stylistic triumphs of the earlier Von Sternberg/Dietrich collaborations the focus shifts to the orient with a kind of Grand Hotel on rails. The cinematic motifs favoured by Sternberg, chiaroscuro effects, painterly framing, fluid camera movements and intricate composition reaches its zenith with this masterful piece. As open a love letter to an actresses face as has ever been committed to celluloid, Dietrich is seen in close up surrounded by feathers, furs and veils, framed in windows or lit from below in shots worthy of the great black and white portraitists of the '20s and '30s. The result is delirious and irresistable, the impulse forgivable and in the process he gave us Marlene as icon, a treasure for the ages.

We open as a divergent crew of travellers descend upon the Peking station for the 3 day ride to Shanghai, braving a countryside torn by civil war. The shots of the train leaving the station are stunning, the sets are busy yet achieve a kind of effortless authenticity. The camera is fluid and the cutting sharp, giving us local colour and context. The main characters converge in 1st class, the American gambler, the British officer, the French soldier and Mr Chang, a Eurasian businessman et al. The talk of 1st class is soon centred around the two ‘loose’ women who are aboard, one is Hui, a Chinese prostitute being run out of town (Anna May Wong) and the other the legendary ‘coaster’ ( a woman who works from town to town along the coast) Shanghai Lil. The British officer, Dr Harvey (Clive Brook) is shocked to find that Lily is a woman he was once in love with, and the two meet again much to his discomfort. Lily affects a kind of ambivalence in regards to their former relationship, making it clear she’s moved on and sheeting home the blame for the woman she’s become to the damage caused by its disintegration.

The train is soon caught up in the civil war as first Government troops arrest a rebel Lieutenant and then the rebels stop the train and take a hostage to trade for the captured officer. The rebel leader turns out to be Mr Chang, who was sharing 1st class with the others. Chang was prone to giving the American gambler (Eugene Pallette) lectures in the local philosophies ‘this is China where time and life have no value’ and the shock him by claiming as a half-breed he wasn’t proud of his white blood. The device of having European actors play Asians was stock for the period and although it sits uncomfortably with modern mores this rendering is fairly benign and Chang is convincingly played by Warner Oland, who even went on to play the Charlie Chan detective character in several films.

Chang settles on taking the Doctor hostage to exchange for his Lieutenant. Lily soon learns that Chang intends to blind the Doctor before exchanging him, revenge for Harvey intervening when Chang tried to force his charms upon Lily. Chang, who’d tried unsuccessfully to seduce Hui on the train, soon brings her forcibly to his chamber during the midnight stop as compensation after failing with Lily. In order to save the Doctor Lily agrees to stay with Chang, thereby confirming Harvey’s lack of faith in her. Only the fallen Hui, regaining her honour by killing Chang gives the lovers one last chance to get past their respective pride and admit that they still love each other deeply.

This is a film where the two central women characters are simply hypnotic, and the men are somewhat sidelined. Brook, albeit wooden and stagey is in the end impotent to influence Lily’s decision, his fate is entirely in her hands. Ironically, in the midst of all the machismo of war it’s the feminine who does the killing and propels us to conclusion through action. Anna May Wong is an incredibly modern presence, mysterious and edgy in a way seldom seen in the early thirties. But it is the strong and independent Dietrich who commands the centre, even when she’s not there. In Morocco, another Von Sternberg masterpiece, she is reduced to a needy husk of a woman by the dashing Gary Cooper, and submits to the patriarchal paradigm by the denouement. Here you sense no man will gain the upper hand with Shanghai Lily, even if appearances suggest otherwise. She is a survivor, as her reaction to Hui contemplating suicide tells us, life at any cost. Sternberg and Furthman (a lifelong collaborator with Sternberg, who went on to form an equally brilliant partnership with Howard Hawks) are not judgemental of Lily in the way you’d expect for the time, even having the Reverend Doctor on the train admit to Lily’s inherent sense of honour after he comes to understand the depth of her devotion to Harvey. Harvey had asked him ‘how do you locate a soul’? earlier and it’s plain he thinks he’s seen into Lily’s, no small consolation in an era where fallen women were to be condemned, not rewarded with happy endings.

The look of the film and the lure of the East struck a chord in Hollywood and even Frank Capra was moved to imitate it with the underrated and superb The Bitter Tea Of General Yen. Shanghai Express is a wonderful ride to take, to a short lived cinematic faux exotica, as this kind of escapist fare from Hollywood was soon to lose favour as the reality of another world war and its legacy changed the landscape forever.