The war lingers on...

By Michael Roberts

“It probably started in poetry; almost everything does.”

~Raymond Chandler on Hard Boiled/Noir

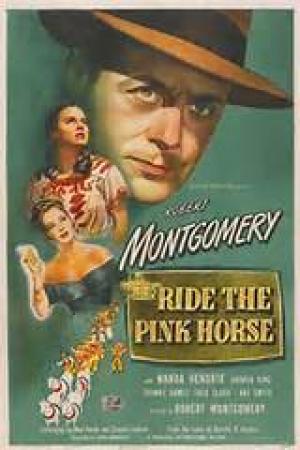

Robert Montgomery was an established romantic comedy star for MGM during the 1930s and had made nearly 40 features before he made an impact in the dramatic film Night Must Fall in 1937. A true Hollywood insider, he was also President of the Screen Actor’s Guild before he served as a Destroyer class officer during the war, an experience that led him to playing his best role in John Ford’s masterful They Were Expendable in 1945. Montgomery showed a serious side to his art with that piece and soon moved into direction with the startling Film Noir, Lady in the Lake, a crime film shot in the ‘first person’, where the action is seen from the central character’s point of view. The film was a success and Montgomery moved to his follow up project, Ride the Pink Horse, another hard-boiled blast based on a novel by Dorothy B. Hughes who also wrote, In a Lonely Place. The prolific and brilliant Ben Hecht adapted the novel for Montgomery and provided a first class script for the second time director.

Gagin (Robert Montgomery) is an ex-GI who arrives in the small New Mexican town of San Pablo intent to avenge the murder of his friend and wartime comrade Shorty. He stalks a mob boss named Hugo (Fred Clark) but is distracted by the attentions of Pila (Wanda Hendrix), a young Mexican girl. He also becomes caught between Retz (Art Smith), a cop who is trying to gather evidence on Hugo for an indictment and who tries to enlist Gagin’s help. It’s clear Gagin is out to blackmail Hugo and set himself up for life with his thirty thousand dollar payout. While waiting for Hugo to organise the cash Gagin gets friendly with Pancho (Thomas Gomez), a gregarious local carousel operator, who takes a shine to the taciturn gringo.

Post war America was a different place for many, and it’s to Montgomery’s eternal credit that he embraced the zeitgeist and made a film that spoke to the national neurosis and widespread uncertainty. Gagin is a man in a post war funk, still full of rage but impotent and flailing in the face of a changing country; he wants his slice of the American dream and intends to take it from the despised war profiteer Hugo. In the gap between the GI’s returning home and the rearrangement of the countries capacity to produce consumer goods, expand into the suburbs and grow the middle class to a satiated plumpness unprecedented in consumerist history, a pall of uncertainty lingered. Gagin is also a man struggling to snap out of the fog of despair that’s compromised his innate decency, a staple of Noir, a condition that has led him to a dark place. Pila offers him a window to an innocence he’s long lost, and the childish whimsy of the central carousel is an underscoring of this concept.

Whilst American Noir was primarily powered by the liberal to leftist brigade of émigré directors like Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak and Jacques Tourneur, et al. it was rare for native political conservatives like Montgomery to notice and adopt a change in tone to suit the times; the ‘darkness’ and hardness that had seeped into the public consciousness, something the French noticed in American movies and retrospectively labelled it Film Noir in the 1950s. Montgomery was a member of the right wing Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, and it may have given fellow members like John Wayne, not to mention rabid red haters like Ward Bond and Adolphe Menjou, pause for thought that Montgomery cast Art Smith in the role of Retz, Smith being a Group Theatre alumnus and Communist Party member. Smith’s career was effectively ended by the Blacklist in 1952, after his former colleague Elia Kazan confirmed his political history by naming him in his testimony.

Ride the Pink Horse also benefits from a sharp performance by Fred Clark, an actor most noted for comedy, but who also possessed a powerful physical presence which Montgomery used to great effect in creating menace and threat. Montgomery subtly accentuates Hugo’s inhumanity and flaws by presenting him with a large, primitive hearing aid wired for sound, a disconcerting look for a modern audience. Gagin is conflicted, arriving in town like a man in a trance with one thing on his mind, blackmail, but Pila helps him emerge from the fog and his dilemma is whether or not to act with integrity once more, even if it costs him a stable future. Hugo sums it up, “People are interested in one thing, the payoff!” as his erstwhile girlfriend Marjorie (Andrea King) tries to cut an even more lucrative deal behind Hugo’s back.

King gives a fine and note perfect performance as the duplicitous girlfriend, and her key scene after dancing with Gagin is deftly handled and quietly shocking in the best femme fatale tradition. Thomas Gomez made the best of the warm hearted Pancho, (and won a Best Supporting actor nomination for his work) and he too reminded Gagin that happiness was not always tied to a payout. Gagin has seen a lot of pain and been told a lot of lies, and promised much by his government as a returning hero, but the reality is different. Gagin’s cynicism is palpable “I seen a lot of flags”, but he’s subconsciously holding out for some decency, dismissing the popular and loose girls at the expensive hotel to Pila as “dead fish with a lot of perfume on ‘em.” Like many Noir heroes Gagin is a good man trying to get out from beneath a hard exterior.

The memorable soundtrack has a delightful Tex-Mex flavour, provided by composer Frank Skinner, who would go on to provide lush and romantic scores for Douglas Sirk’s remarkable Universal cycle in the 1950s. The wonderful cinematography Russell Metty, also a key Sirk collaborator, shot the film with a delicate array of light and dark, and it was Metty who filmed the astonishing Touch of Evil for Orson Welles in 1958, a film that most critics arbitrarily mark the end of the Film Noir era with.

Robert Montgomery is largely forgotten, as an actor most of his legacy is lightweight and unremarkable, but he had a flair and lightness of touch that belied a talent for tougher work. He is seen at his best as an actor in John Ford’s superb, They Were Expendable, and he is so good in that it’s a shame he couldn’t find roles with decent directors to add to that definitive characterisation. He delivers a wonderful turn here as the weary veteran, achieving a convincing aura of quiet desperation and inner turmoil. As a director he showed a touch for the dark and moody side of human behaviour, and Lady of the Lake and Ride the Pink Horse will find a welcoming reception from Film Noir fans for generations to come.

*as usual The Criterion Collection has come up with the definitive version of the DVD, pristine and heartily recommended.