Duvivier returns serve

By Michael J Roberts

“I know it is much easier to make films that are poetic, sweet, charming, and beautifully photographed, but my nature pushes me towards harsh, dark and bitter material”

~ Julien Duvivier

No less an ‘auteur’ than John Ford gave short shrift to any critic brave enough to label him with that moniker, and it seems that the “it’s only a job of work” rejoinder would be one shared by Julien Duvivier, which would have suited the breathless luvvies from Cahiers du Cinema just fine. Duvivier’s reputation, trashed by the writer/directors of the Nouvelle Vague, is undergoing something of a ‘correction’ by modern scholars and a great point to start is Panique, his first film after returning to France post WWII, and one that was critically mauled and commercially rejected at the time. Maybe, like Renoir’s Rules of The Game, it was a little too close to the bone for audiences in 1946, either way it’s the work of a master and deliberately seems to hark back to the Poetic Realist tropes of the 1930s that had made Duvivier’s name, even as it levels an oblique swipe at the ugly behaviour of mob vengeance in a post-collaborationist France.

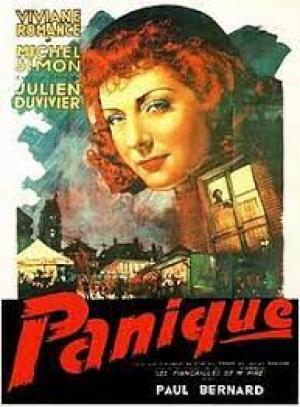

Monsieur Hire (Michel Simon) is a mysterious bachelor who studiously avoids all but the necessary contact with his fellow man. Into his town arrives Alice (Viviane Romance) and his hermitic existence begins to unravel, as Hire watches the woman undress from across their apartment windows and develops a fascination with her. Hire tries to insinuate his way into her life, but Alice is disgusted by him and secretly meets with Alfred (Paul Bernard) her old boyfriend, and the reason she’d come to the town in the first place. Alice has just been released from prison, after doing time because she covered up for Alfred and they keep their past to themselves as Hire works any angle to tear them apart. Against this menage a trois a murder plays out in the small town and suspicion falls on the disliked hermit, but as the community anger starts to boil Hire is preoccupied with the object of his affections, too distracted to see the growing danger.

Duvivier returned from the US to a France reeling in a state of collective Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He had, unlike famous countryman Jean Renoir who’d effectively fled the coming German occupation, already worked in the US for a couple of years before the war and then stayed in the US, for obvious reasons, as the war in Europe raged. He was at once mistrusted because of his wartime absence but also in the unlikely place of being able to provide an outsider’s perspective on the fallout from the disastrous conflict. Duvivier, a noted misanthrope, pulled no punches and was famously quoted as saying, ‘We are far from people who love each other.’ The main themes of the work revolve around betrayal and suspicion, and given the victim of the tale is Jewish, Duvivier was inevitably referencing the infamous Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup in Paris of July 1942, when over 13 thousand Jews were sold out to the Nazis by their distressingly eager and mostly Catholic neighbours.

The source material was the 1933 short novel Les Fiançailles de M. Hire (Monsieur Hire’s Engagement) by Belgian writer Georges Simenon and was adapted by the brilliant Charles Spaak (along with Duvivier), a frequent screenplay contributor for several of the key Poetic Realist directors. The film changes some key components from the already dark book to fit more in line with Duvivier’s even bleaker view of humanity, but the mob’s blood mentality, easy embrace of gossip and casual betrayal, underlines the tensions exacerbated by the pressures of the war. The novel’s setting inevitably evoked a recovery and reconstruction period tension, with a population still recovering from The Great War, unaware there would be a second in less than a decade, but Duvivier need a population that had elements of turning on itself when under stress.

For the titular role Duvivier enlisted one of the icons of French cinema, the Swiss born Michel Simon. Simon had enjoyed a long career as a successful stage actor and eventually transferred that success to the silver screen, working with Vigo, Renoir, Carné and Duvivier in the 1930s in a series of classic films. Simon is superb as Hire, imbuing the misanthrope character with a haughtiness and disdain worthy of the director himself, and giving the film its central fulcrum on which the drama turns. Hire is the centre of the town’s misgivings and insecurities and the mostly unsuspecting mark for the scheming criminality of the scummy lovers. That Simon can bring a sympathetic dimension to this character gives the piece a sense of melancholy as well as an undercurrent of dread that serves to make the studio bound staging quasi-operatic in its intensity and scope.

Viviane Romance is a lovely foil for Simon, a veteran of notable pre-war Duvivier triumphs, particularly as the beautiful schemer in Labelle équipe, and she is ravishing here as the low life Alice, locked in a doomed relationship with a first-class loser. Matching her in putting flesh on the bones of irredeemable characters is Paul Bernard, a strong presence who oozes sleaze and self-interest, like the worst of the black-market profiteers during the war. Bernard had worked for several notable directors prior to this film, including starring in the early Robert Bresson masterpiece Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne but Panique and his spot-on rendering of the odious Alfred remains a high point in his career. The film was superbly shot by experienced cinematographer Nicholas Hayer, who had helmed the seminal, controversial, and eerily similar examination of small-town betrayals, Le Corbeau, for Henri-Georges Clouzot a few years earlier.

Panique was released in an environment where war weary France was still coming to terms with the fallout from collaboration and old wounds and scores were being assessed and settled, sometimes in spectacularly violent ways. Not surprisingly, it failed to find a sympathetic audience and this masterclass in dissection of the darker stains within the human psyche sunk without trace, and only recently has its reputation (along with Duvivier’s) been repaired and its worth as a French masterpiece of the first rank affirmed. Panique remains a quintessential entry in the large and significant arena of films that address the occupation of France and the national identity crisis it engendered.

*The novel was superbly adapted again (more faithfully this time) as Monsieur Hire in 1989 by modern French master Patrice Leconte, starring Michel Blanc and the sublime Sandrine Bonnaire.