New song and dance

By Michael Roberts

"Technical skill counts for nothing if it is used only to manufacture films which have little to do with humanity."

~ Edward Dmytryk

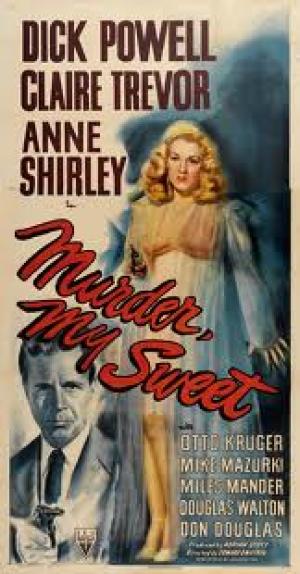

Edward Dmytryk worked his way through the RKO editing room to direction, the same as colleagues Robert Wise and Mark Robson, and like them he started with low budget film noir's, but with Murder My Sweet in 1944 he succeeded beyond anyone's expectations in making one of the great films of the period. Casting Musical and light comedy star Dick Powell against type he tapped into the darker hued tones of the noir ethos and provided a template to frame the sharp and edgy adaptation of Raymond Chandler's anti-hero P.I. Powell's Philip Marlowe may not be as iconic as Bogart's but it ages particularly well, where Bogart played the cynicism and detachment of Marlowe with an air of exasperation, Powell adopted a more laconic approach, and it's the type of modern energy seen in the '70s neo-noir, in outright homage to the form, particularly Robert Altman's superb The Long Goodbye. The casting of Powell led to the studio changing the title from Farewell My Lovely, as they didn't want audiences to think it was a musical.

Murder, My Sweet was adapted by John Paxton, who went on to work with Dmytryk in other significant '40s Film Noir's Crossfire and Cornered, and the writing is crisp, witty and hard boiled. The mood was beautifully captured by cinematographer Harry Wild, a master of the dark moods, and he later contributed to Renoir's atmospheric Noir piece, Woman on the Beach. The film was scored effectively by the prolific RKO house composer Roy Webb, who wrote all the scores for Val Lewton's horror unit productions as well during the 1940s.

Dmytryk starts with a bang, as a very rough and beaten up Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell) is blindfolded and being interrogated and we're not sure why. It turns out to be police asking him questions about a dirty episode and Marlowe proceeds to relate the story as Dmytryk moves to a flashback. Marlowe is hired by an enormous thug called Moose (Mike Mazurski) to track down and old flame, and he reluctantly takes the job, intimidated by Moose's physical bulk and deciding discretion and a fee is the better part of valour. Dmytryk establishes simply that Marlowe is quick witted and pragmatic.

Soon there's a girl, of course, the lovely and decent Ann (Anne Shirley) and the apparent murder of a very odd and possibly gay character who also wanted Marlowe to do some work, this time in the nature of 'protection'. Marlowe feels he hasn't protected the murdered party and sets about to square the ledger by finding out who did the killing. Soon all the threads are coming together with the femme fatale, Helen (Claire Trevor) entering the scene. There's a ineffectual father who deals in rare jade, and a series of odd events that leave Marlowe beat up and sinking into a black pool a little too often.

Powell's playing of Marlowe reflects that of Hollywood's changing leading man values. The old stoicism is making way for a new and conflicted character, not certain of every action and having to come to terms with not only the 'doing', but also the meaning of the 'doing'. This is a move towards the existentialist man, one who has to invest happenings with meaning that resonates for him, most often accompanied by finding a kindred spirit in a woman who can help him make sense of the new and shifting terrain. Marlowe's temptations to stray from the 'path' of course come in the lovely shape of blonde bad girl Helen, but ultimately, for all her allure, he finds the anchor he needs in the arm of the much duller, but steadfast Ann. Powell's Marlowe doesn't exude the taciturn coldness of Bogart's in this regard, he allows his warmth to show and therefore humanises his Marlowe, further differentiating the two portrayals, but both are existential characters in search of meaning. Powell walks away with the acting honours and proved himself a versatile and capable performer, and Claire Trevor's femme fatale is excellent.

The 'Private Eye' movie conventions are well played out, but as this film was one of a select few that helped define them, it's a little more than meeting expectation. Dmytryk has Marlowe underplay many of the scene's and the restraint and wit are a big part of the film's appeal. Powell strikes a match on the arse of a statue of cupid at one point, lightening the mood and giving us a glimpse of a sardonic wit in keeping with Bogart's famous 'bookworm' turn in The Big Sleep. Mazurski's physical threat provides the impetus for Marlowe to cleverly tie up all the ends, and again it's the laconic wit and absolute pragmatism that endears this Marlowe to the audience, who know which way the denouement is heading, but enjoy seeing the idiosyncratic route taken on a familiar journey.

Dmytryk's direction is pacy and clear, and the moods he creates are nicely unsettling and oblique when called for, the ending particularly so. Dmytryk was carving out an excellent career for himself with these superior Noir's when HUAC came knocking in the late '40s and he ended up being the only director amongst the so-called Hollywood Ten and spent months in prison for contempt of congress. Controversially he recanted his unfriendly stance, appeared as a 'friendly' witness and 'named names', amongst them fellow director Jules Dassin who then spent the remainder of his career in exile in Europe. Stanley Kramer, who had his own uneasy experience with the blacklist, and allegedly 'sold out' his High Noon writer and partner Carl Foreman, resurrected Dmytryk's career after his recanting to HUAC and employed him to direct Humphrey Bogart (who did some backsliding of his own in relation to HUAC, see Key Largo ) in The Caine Mutiny. Interesting times.