French return serve, Melville does Noir

By Michael Roberts

I'm not a documentarian; a film is first and foremost a dream, and it's absurd to copy life in an attempt to produce an exact recreation of it. Transposition is more or less a reflex with me.”

~ Jean-Pierre Melville

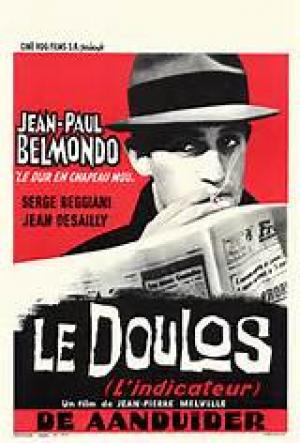

Jean-Pierre Melville sailed through the Nouvelle Vague era as its (somewhat reluctant) Godfather like figure, blessing it implicitly by taking a cameo in Godard’s ground zero offering, Breathless. After Godard’s breakthrough Melville cast its leading man, Jean-Paul Belmondo, as a priest in his war time thriller Léon Morin, Priest, and followed up the next year by casting him again as a gangster in this taut policier, the stylish and atmospheric Le Doulos. Melville employed Serge Reggiani to play opposite Belmondo, giving the piece a duality that informs the central trope i.e. the quandry of men outside the law who carry their own code. Monique Hennesey plays Thérese, a rare feminine presence in a markedly masculine world, and Jean Desailly plays the dogged Superintendent Clain, pursuing the men who choose to live on the edge of society.

Melville starts with the murder of a fence by Maurice (Serge Reggiani), payback for a betrayal of loyalty, setting the tone for this existential treatise on friendship and moral relativism in the criminal underworld. Silien (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and Maurice “my friend, until proved otherwise” dance around each other while a series of assumptions and suspicions serves to fracture any relationship they may have had. Silien beats Maurice’s girlfriend, Thérese (Monique Hennesey), after a proposed heist is compromised and Maurice assumes Silien has sold him out to Clain (Jean Desailly). Clain closes in and the pressure builds as the two thieves look to square accounts.

As with the best traditions of Film Noir, the atmosphere is redolent with fatalism and thick with menace and threat. The title of the film is a double layered clue as to the concerns of the narrative; it can refer to a hat, a hatted man, or someone with something to hide, also to a ‘finger man’, a criminal low-life or informant. “One must choose to lie, or die”, is the opening philosophical gambit, informing the angst that accompanies the central characters, and it’s book-ended by the stray thought, “In this business you end up a bum, or dead.”

‘Honour amongst thieves’ is one of the oldest adages in storytelling, but Melville complicates that concept by making a film where he said, “All the characters are two faced, all characters are false”. As if to visually underline this trope Melville makes good use of mirrors in the opening and closing sequences, remarking upon the device, “A man in front of a mirror means a kind of stocktaking.” Of course, like the best noir’s, Silien is scheming to escape a murky past, attempting to find a freedom and re-birth but only on his terms, and only after debts have been extracted. The narrative takes some unexpected twists and turns on order to subvert our expectations, but Melville stewards the project superbly, extracting ambiguity and atmosphere with stunning visual panache and effortless wit.

Belmondo totally inhabited the detached and cool character of Silien, a fatalist of the highest order and a decided contrast to the quiet and thoughtful role of the priest in his previous Melville film. The actor was enjoying a strong run after his debut feature, À double tour, and was well established by this, his 10th feature, already having filmed several timeless classics with Godard, Chabrol and Melville. Belmondo, perhaps more than any other actor, embodied the new, modern French male, more ambivalent or intelligent, rather than the brute leading males like Jean Gabin or Michele Simon in times past. Melville uses the accomplished actor and soon-to-be star of French cinema, Michel Piccoli in a small role, who injects a stolid presence to a crucial role, hinting at the glories to come with Godard and Buñuel in the next few years. Melville also used noted comedian Desailly in a rare dramatic role, two years before Truffaut used him as a middle aged writer in love with a younger woman in The Soft Skin.

Le Doulos is the last identifiable homage to Film Noir in Melville’s canon, a restatement of the tone and tenor of his wonderful Bob, Le Flambeur, and an indication of the lasting American influence of masters like William Wyler and Robert Wise. Melville made four more policier’s before his premature death at age 55, but they represent a flourishing of his own signature styles rather than homage. Le Doulos shows the growing influence of the New Wave, and Melville taps into the poetic dimension of the French artistic character, a component that would increase with the archly poetic crime piece Le Samurai a few years later.

Le Doulos is a remarkable and compelling Noir, a fatalistic slice of Gallic underbelly from an auteur who never compromised one jot to trends, even when the trend was lionising and worshiping him.