Nouvelle Italiano

By Michael Roberts

"Realism is a bad word. In a sense everything is realistic. I see no line between the imaginary and the real."

~ Federico Fellini

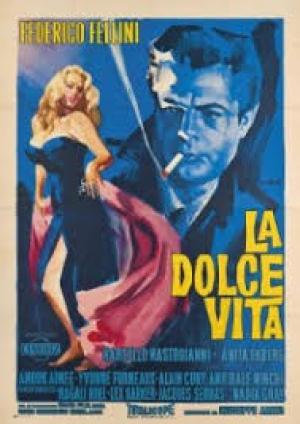

Federico Fellini won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film on four separate occasions, incredibly La Dolce Vita, his coruscating examination of the Roman ‘sweet life’ did not figure in this golden bounty. Fellini had met Marcello Mastrioani when he was working in a play with Fellini’s wife, Giulietta Masina, over a decade before and finally cast the young actor in the lead role of a conflicted writer, torn between higher ambition and low gratification. Fellini made a satire of the international co-productions so prevalent in Europe, the so-called ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ phenomenon of the 1950’s, and fittingly shot most of it in the glorious confines of Cinecittà, the sprawling studio complex that had made many of those co-productions possible. Fellini cast three lead actresses opposite Mastroianni, Anouk Aimée as the bored socialite, Yvonne Furneaux as the needy girlfriend and Anita Ekberg as the Hollywood star. Fellini also used his trusted and regular collaborators in cinematographer Otello Martelli and composer Nino Rota.

Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) is a reporter operating in the pop culture cesspool of Rome’s beautiful people, most of whom are desperate to attach themselves to any visiting international movie stars working in the Eternal City. Marcello encounters his wealthy lover, Maddalena (Anouk Aimée) and together they pick up a street prostitute and go back to the streetwalker’s cheap apartment and make love until dawn. Marcello gets into trouble from his suicidal girlfriend Emma (Yvonne Furneaux) but he leaves her in hospital to pursue a glamorous starlet, Sylvia (Anita Ekberg). Marcello is torn between his ambition to write literature and the easy, seductive rut he’s fallen into before his dilemma is further accentuated by an encounter with Steiner (Alain Cuny), a successful intellectual and later with his own father. Marcello continues to struggle against the ephemeral delights of the ‘sweet life’ and the urge to find a deeper meaning beyond the glitterati.

Fellini opens the film with the visually striking image of a Jesus statue being transported across Rome via helicopter, an immediate shorthand for counterpointing the sacred and the profane, the modern and the ancient. La Dolce Vita is an examination of the distance between apparent opposites, of the emptiness at the heart of the ‘sweet life’ and of the sadness inherent in life where the possible is somehow impossible. Fellini constructs a series of encounters in Marcello’s life to unpack this dichotomy, and bookends his dilemma with encounters with women, seemingly within his reach but where communication is compromised, if not impossible. Between these bookends he thrusts his protagonist into a succession of sexual or emotional encounters that both fulfil and frustrate the handsome writer. First of these is his night with Maddalena where the rich heiress is bored and uses him as a distraction and accomplice to pick up a prostitute. Maddalena gets her kicks by making love in the prostitute’s cheap and flooded apartment while the hooker sits outside drinking coffee, and Fellini leaves open the possibility (as much as anybody could in Catholic Italy in 1960) that she could join in! The divide between rich and poor may be stark, but the connection between classes in utilisation or exploration of the corporeal, of the profane to merely exist is undeniable. The prostitute screws for money, the heiress out of perversion or boredom, Marcello out of lust and emptiness and it’s the transactional, not redemptive power of love that Fellini seems to be showcasing.

Marcello’s next encounter is with his unhappy girlfriend Emma, driven to a suicide attempt by his repeated infidelities. Even as he’d comforted her on her hospital bed, he left her to call Maddalena, then set off in pursuit of the latest starlet to arrive in Rome, the buxom beauty Sylvia. Marcello finds himself alone with the starlet and they spend a night on the streets of Rome before Sylvia jumps into the Trevi fountain for a famous sequence. Fellini is satirising the fact that Hollywood was taking advantage of the cheap costs in Italy to make some films there, which resulted in the ‘sword and sandal’ cycle and later the ‘spaghetti western’. Sylvia baptises Marcello into the cult at the end of their reverie and that sets up an internal conflict in the writer that plays out in the next encounters. Marcello meets his friend Steiner, who plays Bach on a church organ and encourages him to write the book he has ambitions to write, to embrace the higher world of literature over the tawdry scrum of paparazzi driven journalism, forcing Marcello to confront the emptiness at the core of his existence in light of Steiner’s seemingly blissful, full and perfect life, one that the ‘mothering’ Emma suggests is available to Marcello. More Catholic symbolism is again invoked at the end of the film where Marcello kneels as he faces his ‘Umbrian Angel’, and where Fellini placed him in a position of power, oozing confidence in relation to the bikini-clad women at the start of the film, i.e. in a helicopter and elevated to the level of the flying Jesus, here he is a shell, wrecked and unsure, looking for redemption but unable to recognise it when he sees it.

In between Marcello’s episodic and rambling doings Fellini injects a subtle appeal to innocence by having children enter the picture at various levels. We see children innocently acting out adult delusions in a remarkable and chaotic sequence involving visions of the Blessed Virgin, a common enough occurrence in Catholic Italy to this day. We see Steiner’s children as creatures of purity and peace as he kisses them goodnight in a tender ritual observed by Marcello. Fellini lastly shows a young girl in transition from child to woman who is working in a small cafe where Marcello sits at a typewriter – the scene is deliberately set apart from the rest of the film in tone and texture, dappled sunlight emphasises the spare, stripped back nature of the encounter where stillness and light is a palette cleanser to Marcello’s regular, dark urban frictions. Fellini tantalises here; Is Marcello finally writing his novel? Is the “Umbrian angel” the answer to his endless womanising and a pointer to a future he covets, one like Steiners? The peace is short lived as Marcello falls even deeper into the ‘sweet life’ and even the jolt of the Steiner murder-suicide can’t alter his trajectory. Fellini concludes with a resolution that suggests Marcello is a washed-up, dead-eyed sea creature, blankly stumbling from one decadent distraction to another, unable to communicate with the half-remembered, pure hearted and gentle redemption on offer just out of his reach, Fellini shows him kneeling like a penitent but drawn inexorably back to the soulless, emptiness of the 'sweet life'.

La Dolce Vita is a structural masterpiece, unfolding in a set of vignettes that essentially suggest a cycle of dark and light, set across a series of encounters that generally transit from night to day. The night circus holds the action, the passion, a repository of freaks and fools and the cold light of day holds the reckoning. It is without doubt at the top of Fellini’s masterwork’s, its existentialism suggests Bergman, its visual flair is worthy of Kubrick, its cynicism does justice to Wilder and yet it’s entirely original. Great artists are explorers and in reaching their destination it is necessary to make the journey in stages, one point reached allows vision of the next possibility (or dead end) and so La Dolce Vita is a key transitional film, in that 8 ½ could not have come after Nights of Cabiria or Il Bidone, in the same way The Beatles could not have leapt from the pop glories of Help! to the ‘future-starts-here’ jolt of Revolver without the boundary pushing Rubber Soul pointing the way.

Fellini was at the height of his powers and acclaim during the making of the film, and paradoxically he was also battling with depression. Despite the resultant successes and travails, which included a fight with the Catholic Church over censorship, Fellini fell into a kind of ‘writer’s block’ and when the time came to make his next film he was artistically frozen. Fellini’s solution was ingenious - turn inwards, embrace his dilemma and express it artistically, which he did in the startlingly modern 8 ½. In a few short years Fellini had moved from the Neo-realism of I Vitellone to the quasi-impressionist genius of La Dolce Vita, with the full-blown impressionism of 8 ½ now possible, helped on by a liberal dose of Jungian dream theory and LSD! Just as The Beatles made the miraculous leap from Love Me Do to A Day In The Life in less than 5 years, changing music and popular culture in the process, so too Fellini’s in his field. La Dolce Vita is not only a key piece in an artistic puzzle it’s also a beautiful rendering of the artists dilemma, and a reminder that cheap thrills and artistic integrity don’t always co-exist.

La Dolce Vita is a line-in-the-sand film, a poetic, clear-eyed, cynical existential masterpiece and just as his contemporaneous peers and scions of the Nouvelle Vague (Godard, Renais and Truffaut et al) were doing, Fellini was also saying, ‘modern film starts here’.