The Kids are not alright

By Michael Roberts

"Great pictures can't be entirely fictitious." ~ William Wyler

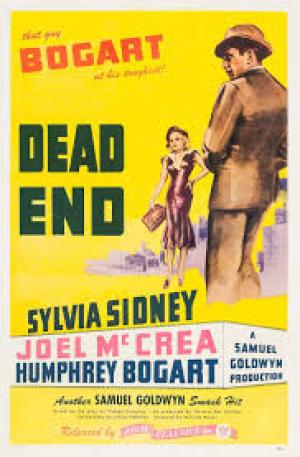

An early high-water mark, during a particularly fruitful collaboration between William Wyler and producer Sam Goldwyn, was the production of Dead End, a successful Broadway play by Sidney Kingsley, adapted to the screen by Lillian Hellman. Goldwyn got then second-line Warner’s contract player Humphrey Bogart to reprise his stage role of Baby Face Martin, a gangster part that was more complex than the type Warners were using him for, and also teamed up Joel McCrea and Sylvia Sidney to lead an excellent ensemble cast in the gritty pre-Noir masterpiece. Wyler further enhanced the films prospects for greatness by using master cinematographer Gregg Toland to shoot the piece, on a superb set designed by Richard Day.

Drina (Sylvia Sidney) is a young, decent girl trying to keep a roof over the heads of her and her younger, semi-delinquent brother in the poorer part of the East River. She is active on a local picket line, trying to better her meagre wage and has a crush on a local man Dave, (Joel McCrae), an aspiring architect who can’t catch a break, but he, in turn, is smitten with a glamourous woman living the high life in neighbouring, up-market apartments. The area is full of slum kids, bored, itinerant youngsters who pick fights with anyone and everyone. Into this urban crush waltzes ‘Baby Face’ Martin (Humphrey Bogart), a notorious killer who is on the run from the law. He’s had his face surgically changed and wants to see his mother again and meet up with Francie (Claire Trevor) an ex-girlfriend, trying to reignite an old flame before he goes into permanent hiding. Dave sees the kids idolise the gangster and tells Baby Face he’s not welcome, on his old home turf.

In many ways, Dead End may be the least dated 1930’s film of any kind - Its visual language is still fresh, taut, moody and stylish, worthy of Von Sternberg and its central concerns about the ‘haves and the have nots’ are timeless. Notwithstanding the visual elegance and the intricate, layered world that Wyler and Toland concoct, it fundamentally skewers the abiding furphy that America is a classless society where the individual succeeds solely on the merit of his or her own effort. To have a central, sympathetic character proudly proclaiming her time on a picket line, wearing blows from the police, at the height of the Great Depression was a rarity in the mainstream Hollywood cinema of the time. Set at a time when the US was avoiding falling into fascism by Roosevelt’s New Deal (denounced, to this day, as ‘socialist’ by the conservatives on the right) Kingsley pointedly sets his story at the intersection of great wealth and great poverty, as grand and expensive apartment blocks started to squeeze out the slum tenements on the East River.

Multi-dimensional examinations of social inequality are not the first thing that comes to mind when considering 1930’s Hollywood, yet some key moments of that cinema legacy involve just that, mostly as Robert Riskin scripted fables directed by Frank Capra. The fabulous lives of the wealthy were often presented as a kind of dream, where the right person from the wrong side of the tracks could end up living the good life. After all, the impulse to assuage a guilty conscience and give the poor a taste of opulence was Nelson Rockerfeller’s stated inspiration for building the grandest Picture Palace of them all, Radio City Music Hall. Considering the Depression had created great suffering, at the other end of the scale you also had a class of people that were recession proof, as the gap between rich and poor was stretched to record levels. That trend stalled after the redistribution of wealth in the wake of the great middle-class gains in standards of living after WWII, where a phenomenal consumer led recovery changed the face of America. This model held until Reagan in the 1980’s where the Neo-cons, and the rising corporatocracy conspired to siphon most of the profits to the top end of town, with the lie that the entire country would benefit because of the now discredited concept of ‘trickle-down economics.’ The result of that unholy pact is that inequality in the USA in the early 2020’s under President Hyperbole has risen to levels not seen since Dead End was made.

Almost 20 years before Alfred Hitchcock’s justly celebrated set for Rear Window, the Richard Day designed set for Dead End is simply a wonder, and a reminder of the artistry in the studio system that produced it. Toland and Wyler make great play in a sequence of complex camera moves, teasing out all the intricacies and contrast on offer as they frame the conflict and situations on screen. A simple pan upwards can take us from the kids burning scraps in the street to keep warm, up to the lofty outdoor balconies where the rich party on, oblivious and without a care. As much as the vibrant environment, it’s the human interactions that stay in the memory. There is a startling scene between Marjorie Main (yes, Ma Kettle) as Baby Face’s mother and the gangster when they reunite, but it’s as hard as nails, as is Martin’s uncomfortable reunion with (Claire Trevor). The code of the time prevented a direct reference to her condition (syphilis) or her profession (prostitute) but Bogart’s reaction and Trevor’s dexterity leave us in no doubt in a scene so powerful that Claire Trevor won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for a screen time of 5 minutes.

Sylvia Sidney was an actress of her times, a genuine star in the 1930’s but her persona seemed so wedded to that period and her presence so ethereal that she didn’t transfer it to other decades, even though she appeared in film until the 1990’s. She starred opposite many of the major male stars of the thirties, and her delicate presence graced many a fine film, including You Only Live Once, a gorgeous pre-noir by Fritz Lang opposite Henry Fonda, also in 1937. Joel McCrae was an ideal pairing for Sidney as they both oozed an ordinary decency, the antithesis of MGM glamour or Warner Bros hardness. McCrae's star was almost at its zenith in the late '30s after several years of graft and hard work, and his charming and warm everyman persona was never used to greater effect than here. Willian Wyler had recognised his qualities the year before, in the stylish drama, These Three, a superior adaptation of Lillian Hellman's, The Children's Hour. The immortal Bogart was still to graduate to his classic leading man period, and Warners lent him to Sam Goldwyn for the Baby Face Martin role he'd played on stage in New York, even though Goldwyn originally wanted George Raft for the role, who turned it down, setting a pattern where Bogart picked up his juicy rejects, including crucially, High Sierra.

William Wyler proved himself a master director with These Three in 1936, after serving an apprenticeship with more than a decade of helming low budget fillers, but he quickly consolidated his standing with a series of superb films, including Dodsworth, Jezebel, Wuthering Heights, The Westerner, The Letter, The Little Foxes and Mrs Miniver, before World War 11 intervened and he set off for Europe in uniform. Frequent Wyler collaborator Lillian Hellman wrote the razor sharp screenplay for Dead End, and Gregg Toland shot the memorable visuals, one of six films he made with Wyler between 1936 and 1946. Wyler was a consummate artist, able to bring together the intricacies of story, look and performance to create cinematic works of art to stand the test of time, and Dead End is able to stand with the best of them.