O'Toole's tour de force

By Michael Roberts

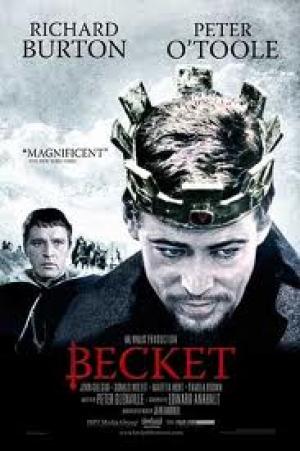

Peter Glenville’s 1964 ‘historical’ drama Becket more closely resembles an old school producers film than an auteur piece, even if it’s filming coincided with the rise of the director-as-star era of the Nouvelle Vague. Veteran Hollywood producer and Warner Brothers legend Hal Wallis wanted to end his career with a prestige project, having spent many years shamelessly exploiting Elvis Presley’s popularity in a series of films of dubious quality. Wallis took the time honoured course of purchasing the rights to a Broadway hit play and then went looking for the best actors of the generation to cast in a film version. Wallis looked at a rough cut of Lawrence of Arabia and knew he had found his star in the gloriously talented Peter O’Toole, he also knew he had to match him in talent in the title role opposite and wisely he turned to the brilliant stage actor Richard Burton.

King Henry II (Peter O’Toole) of England is juggling his royal responsibilities, trying to keep his tax revenue high enough to run a war with France, keep the Church subservient to the King and its powerful bishops in check. In between bouts of whoring and drinking with his Saxon friend Becket (Richard Burton), Henry convinces Becket to take the seal of Chancellor of the Exchequer, effectively giving Becket control of the countries finances. The pair head off to France to annex some territory from Henry’s mortal enemy King Louis VII (John Gielgud) and whilst there they are informed the Archbishop of Canterbury has died, creating a vacancy. Henry is convinced a masterstroke would be to install Becket as the replacement and, against his better judgement, Becket accepts. Becket soon grows into the role and it quickly becomes apparent that issues of church and state are not easily resolved when both parties have deeply held and opposing positions.

Becket is a wonderful affirmation of the theory that movies work when a great script is given to great actors to execute. Glenville was an experienced theatre director and the troupe treated the piece as they would a West End run, blocking and rehearsing and shooting in sequence. Glenville’s work was made infinitely easier by the quality of the script, a quasi-historical text by French playwright Jean Anouilh which crackled with biting wit, and his familiarity with the piece having directed Laurence Olivier in the Broadway run 3 years earlier. O’Toole was to have done the part of Henry in the London run, but opted out after David Lean offered him a lead role in a certain desert based story.

Anouilh explored the inherent drama of an enlightened protagonist embarked on "a moral path in a world of corruption and manipulation." He plants the seed of the problem between the two friends, an historical conceit but great dramaturgy, as the result of a pact involving a woman that Henry exploited to his own advantage, which ultimately lead to a tragedy that caused the seemingly ice-cold Becket much turmoil and heartbreak. The actual conflict was based on much firmer historical ground, the divide of power between Church and state in a highly religious country where Rome was always operating in the background. Anouilh centres the dispute around the notion of honour, a characteristic that Becket feels he lacks until his King provides him with an unexpected chance to peel back the layers of cynicism and corruption and to live up to the lofty ideals of his office.

Becket tells Henry, “Where honour should be in me there is only a void”. The full title of the play is Becket - The Honour of God, and honour of various stripes is the central theme of the work, and one that is inextricably melded to political intrigue and secular power struggles. Henry continued to battle for a rule of law that excluded the archaic notion of the clergy being immune from secular courts, trying to bring them under the law of the land, “One justice, the King’s”!, whereas Becket continued to support the system of ecclesiastical courts, effectively giving the Pope the last say in prosecuting clergy. Henry assumed Becket would be his man, but Becket made a journey from ultimate pragmatist to man of principle, thus putting a thorn in Henry’s crown. Becket also moved from the status of Saxon collaborator in a Norman court (historically inaccurate) “one collaborates to live”, to a man who instinctively knows he must fulfil an absurd destiny, aware of the irony of his dance of honour.

As good as Burton is in the title role, O’Toole simply dominates the screen with his cracking portrayal of the narcissistic monarch. O’Toole eats the words with a rare relish, spitting out cadences of spite and venom with a delicious verve, serving up one of his great virtuoso turns. The famous quote, “Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest”? is justly famous, but the preceding dismemberment of his wife and family is equally superbly done. O’Toole offered that he and Burton were on their best behaviour for the shoot, for the simple reason that each of their great theatrical mentors were in the cast! John Gielgud had taken a young Burton under his wing and Donald Wolfit had done the same for O’Toole, so both of the stars were eager to be on their game for their idols and friends, swearing off the booze for most of the shoot. Gielgud and Wolfit provide first class support, as does the raft of fine British actors that fill the remainder of the cast, particularly Pamela Brown (Director Michael Powell's lover for decades) as Henry’s put upon wife. Henry’s behaviour towards Becket approximates that of a jilted lover, and his acid tongued mother hints at an ‘unnatural’ relationship. O’Toole underplays this aspect, presenting Henry as a desperate man in need of connection, endlessly testing the depth of Becket’s devotion and trust.

Becket is a record of two first rate actors in major roles at the top of their game. No one does costume drama as well as the Brits, and Becket is full of the best of the genre, superb costume and sets, all exquisitely shot by veteran cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth, who would go on to win an Oscar for 2001 A Space Odyssey, and a posthumous Oscar for Polanski’s Tess. The stage may have seen the best of these great actors in the long run, but O’Toole and Burton etched a mighty powerful raft of memorable screen roles between them, and in the first rank of their number lives Becket and Henry. O’Toole would revisit the Henry character a couple of years later in the equally fine The Lion in Winter, but Burton would only pull on the costume tights a couple more times on screen, battling with his wife Liz Taylor in The Taming of the Shrew in 1967, and as Henry VIII in the Hal Wallis produced Anne of a Thousand Days in 1969. Wallis was vindicated with Becket, a huge hit and a massively honoured piece for the quality of writing and acting.