Dark angel

By Michael J Roberts

'Beyond the beauty, the sex, the titillation, the surface, there is a human being. And that has to emerge.'

~ Jeanne Moreau

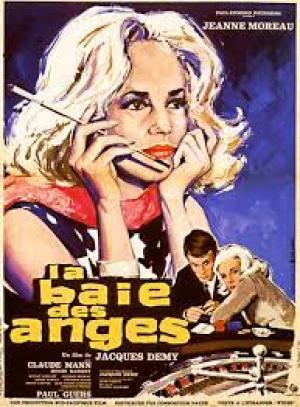

In the early flush of Nouvelle Vague success, a few oddities were thrown up by aspiring French Filmmakers riding the wave for all they were worth, including Jacques Demy. Demy had made several short films and found an opportunity in 1961 to make his quirky debut feature, Lola starring Anouk Aimée, a success which led to Bay of Angels in 1963, his second feature. He secured Jeanne Moreau, then at the height of her fame and coming off her signature turn in Truffaut’s masterful Jules et Jim and cast her against relative unknown Claude Mann in a gambling tale set in the Riviera. The mix of fatalism and arch-romanticism harks back to the glory days of French Poetic Realism and to masters such as Duvivier and Carné

Jean (Claude Mann) is a Parisian bank clerk, bored and aimless until his friend Caron takes him on an evening in a Belgian casino. Jean is intrigued enough to slot some time on the Riviera where he can explore the extent of his new-found obsession. There he sees Jackie (Jeanne Moreau), a woman who he’d previously seen thrown out of the Belgian casino and they strike up a relationship. Over the course of a short period of time their situation escalates into romance and turmoil.

Jean’s fascination with gambling and his eager exploration of it runs counter to his steady life and workaday habits, but even as his own conservative father warns him of the perils, Jean ignores him and heads south to hit the tables. Jackie represents as much as escape from reality to him as the spinning roulette wheel, and he decides he’ll take his chances with both. Jackie’s chequered past soon intrudes and it’s clear that their relationship has an unexpected third party – effectively they are in a ménage à trois with gambling.

Demy, who knew nothing of gambling, wrote the screenplay and was able to incorporate the milieu into a romantic trope where lovers are insecure or duplicitous, as liable to turn on a whim like the turn of a card. Moreau’s ethereal beauty captivates as only she can, but she is a glamorous façade hiding a damaged and brutalised interior, made hard by years of addiction to the tables. Jean is the dilettante here, dabbling in a world where he has little experience but feeling both the pull of the thrill of the punt and the repulsion of the hold it has over him and the person it is forcing him to become.

The film is an homage to Jeanne Moreau’s beauty and presence, in the same way Louis Malle made use of her poise and charisma in The Elevator to the Scaffold a few years prior. Moreau is the fallen angel at the heart of the film, a fleeting vision of promise and grace, and a siren temptress who can only deliver misery and heartache to those drawn to her song. Demy peels back Jackie’s story layer by layer for Jean as he shares with the audience the depth of her fall and the cost of her addiction. We learn that Jackie has given up her husband, her children, and her self-respect in chasing the cards and won’t draw the line at anything that gets in her way of feeding her addiction. She’s a beautiful shell, held together by sheer determination and willpower, but quietly disgusted at what she’s become. Claude Mann is fine as the restrained and conflicted Jean, but it is Moreau’s tour de force and everything he needs to do is in reaction to her, inverting the typical power dynamic in the gender roles of the time. Moreau is simply stunning and it’s hard to imagine this film working so well with any other actress in the central role.

Demy shies away from the sociological implications of the gambling industry, focusing instead on the addiction and the damage it does to the individual. The unseen hand of the powers that run and profit off the misery and sickness of others is not commented upon – the odds are with the house and the house is a sacred temple, run by an unquestioned and invisible hand. Demy is interested in what compulsion drives people to do damage to themselves, to the extent that they can knowingly destroy their own lives, the central tragedy being that they are powerless to stop. The settings are glamourous, Lady Luck is dressed to the nines, the story is personal, and the fates are at play – observed by a cool, detached eye, raised eyebrow and Gallic shrug. Demy employs a beautifully ornate musical score by Michel Legrand, but it has a clarity and intensity that reflects the bubbling underbelly of fear, loss and fate.

The film is splendidly shot by Jean Rabier, a cinematographer who worked almost exclusively for Claude Chabrol during the 1960s, and the moody black and white and austere casino ambience is leavened by sunlight and shadows as the couple escape the prison confines of the tables and real love seems a possibility. Rabier had worked with Demy’s wife, Nouvelle Vague director Agnès Varda on the groundbreaking hit Cléo from 5 to 7 the same year and would go on to shoot the colourful musical (and possibly Demy's most recognisable work) The Umbrellas of Cherbourg with Demy a year later – the complete antithesis of this film, maybe they both needed a change of air after the intensity and fatalism of the haunting and cynical Bay of Angels.

Jeanne Moreau went on to solidify her spot as a movie star for the ages and one of the key figures in French cinema, whereas Claude Mann dropped off the radar almost completely. Demy would have a mixed career of quirky near hits and absolute bombs as he struggled to recreate the clarity of his early work, but Bay of Angels stands as a beautiful testament to his sense of things, in all their glory and all their terror. It's a gem.