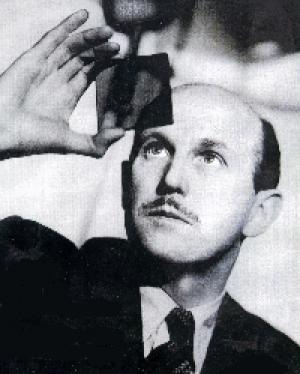

English wizard shoots arrows of desire

By Michael Roberts

"All art is one, man, one!" ~ Michael Powell

Michael Powell rose to prominence in the early 1940's after serving a long apprenticeship in the 'quota quickie' era of the thirties where British films were mostly cheap afterthoughts to pair with the latest Hollywood productions in the fleapits and movie halls of Great Britain. As a younger man Powell had cut his teeth at the end of the silent era as a general dog's body on the unlikely French located sets of Hollywood silent figure Rex Ingram, then running a European office for MGM. Powell longed for film to be a canvas upon which an artistic collage could see a confluence of image, music, movement and theatricality all combine to make a potent art form bursting with new possibilities.

In 1936 Powell began the long process of crystallising his vision with the remarkable and personal The Edge of The World, but it was in the fortuitous teaming with Hungarian émigré Emeric Pressburger, at the behest of legendary producer Alexander Korda, that Powell found a sounding board and talent to match his own, and together they formed a production company called The Archers. Pressberger's keening mind brought an intelligence and depth to match Powell's eccentricities and committment to 'total' art, and the results were pure alchemy, a partnership that created more than the sum of its parts. The partnership was forged in the furnace of World war Two, a calamity that spurred the pair on to signal achievements in British cinema, but as the impetus from that great struggle receded, so to the effectiveness of the Archers.

Powell's work is marked with a kind of peculiar 'Englishness', a way of revealing insights through oblique and sometimes contrary methodology, but always with a great love for his subject, the common British man and woman. Powell lived and breathed 'art', for him life was an adventure and cinema a way to tell stories, and his imagination and flair for the medium was undeniable. WWII provided the opportunity to comment on his beloved nation and their grace under pressure. In a bizarre twist the Archers fell foul of Winston Churchill himself with their wonderful, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, which dared to show a common humanity between an Englishman and a German when the government was determined to demonise the 'hun' at every opportunity, a similar scenario to that Jean Renoir faced with Grand Illusion.

The immediate post war years saw The Archers at the peak of their powers, with A Matter of Life and Death being a neat valentine from the English to the Yanks for belatedly joining the fight against fascism, and the beauty and poetry of the remarkable Black Narcissus, an exhilirating examination of colonialism and cultures clashing. Powell finally moved into the ultimate expression of his personal vision, an intensely visual representation of his cinematic art in the incredible The Red Shoes , much misunderstood at the time and a critical and box office failure by the standards the Archers had previously enjoyed. The film has since come to be regarded as a classic, and its influence resonates to this day. Powell continued to essay the British condition, with smaller and still interesting films like The Small Back Room and the stunning and under-valued Gone To Earth, and also with the archly theatrical Tales of Hoffman.

Powell split with Pressberger after a couple of lesser efforts and then showed he was a true eccentric, and a little too far ahead of the game with the remarkable Peeping Tom. The notoriety surrounding the film essentially ended his career, finishing in features with a couple of surprising efforts in Australia, the very odd They're a Weird Mob, and the under-rated The Age of Consent, with a young Helen Mirren in 1969.

After the Peeping Tom scandal Powell's reputation languished until his younger champions Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola resurrected his critical standing by screening Peeping Tom at the New York Film Festival in the late '70s to great acclaim. Coppola gave him a job lecturing to younger filmmakers at Zoetrope in the early '80's. Michael Powell now sits unreservedly in the top pantheon of British directors, and any conversation regarding the relative merits of Hitchcock versus Lean will soon find someone chiming in with, "And what about Michael Powell"?! A fitting fate for a true English original.

Also recommended;

Battle of the River Plate

The Small Back Room

The Edge of the World

49th Parallel

Tales of Hoffman

For Fans Only;

Ill Met by Moonlight

Best avoided;

Oh Rosalinda